Archive for October, 2023

Artists are leading the way in the transformation of a broken world

“So much of the work of oppression is policing the imagination.”

Saidiya Hartman

When I look at, amongst other traditional landscape paintings, The Hay Wain, created by John Constable in 1821, I observe with nostalgia the artist’s representation of clean, pesticide-free water, pollutionless skies, thriving trees and a small, unobtrusive cottage on the bank of the river the horses and wagon are crossing—a semi-pristine land with humans in harmony with Nature. Landscapes help define a nation and its individuals.

Fast forward to July 4, 2022, and two climate/biodiversity activists have adroitly superimposed a 21st-century equivalent of that bucolic river scene on Constable’s original; in that rendition, a plane flies overhead, the trees are dead, there are ugly skyscrapers and a belching smoke stack, and finally a large truck comes up the polluted river. Tragically, there are now many local landscapes that echo this dystopian image. Meanwhile, there truly is not one toxic-free river in all of Britain in 2023, and ecological systems are in a devastating free-for-all.

Now transform any of the landscapes of the Canadian “Group of Seven” painters, or Québécois Fredrick Simpson Coburn’s landscapes with horses to have a similar outcome, and you get the idea: we have created “the ecological rift” between humans and the rest of Nature, discussed in an important book of that name by John Bellamy Foster, Brett Clark and Richard York. The authors write: “The planet as we know it and its ecosystems are stretched to the breaking point. The moment of truth for the earth and human civilization has arrived.”

Now think about Nature poets like Wordsworth or Keats writing 200 years ago and transform them into contemporary eco-poets such as W.S. Merwin, who penned:

All the green trees bring

from “To Ashes”

their rings to you

the widening

circles of their years to you

late and soon casting

down their crowns into

you at once they are gone

not to appear

as themselves again

On to music, and remember Vivaldi’s Four Seasons for solo violin and orchestra, but turn it on its melodic and harmonic head and you get Frank Horvat’s Auditory Survey of the Last Days of the Holocene, where in one segment you can hear trees being cut done with a chainsaw in the background: https://tinyurl.com/auditory-survey

Tchaikovsky’s 19th-century ballet Swan Lake was recently metamorphosed by contemporary French choreographer Angelin Preljocaj into a struggle to save swans and lakes from the capitalist machinations of an oil baron’s fossil fuel dreams: https://tinyurl.com/swan-lake-transformed

Let us heed the call of artists. Artists have always been at the forefront of society. The arts give us the imagination and the guts to turn around these most dangerous times in humanity’s history. See, hear, sniff out, listen and by all means taste what they unreservedly spread before us.

Eighteen Québec universities have come together to hold six free online sessions on different aspects of climate every Wednesday at noon until November 22 in order to give citizens an all too brief foundation in climate education. It is a beginning. The first of these webinars took place on October 18 and gave us the historical background to the annual United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP), including excellent graphics for the upcoming COP28 meeting to be held in Dubai from November 30 to December 12. Other webinars will focus on such critical climate topics as forests, oceans, climate justice, water, agriculture, energy transition, eco-finance, and the role of cities in climate mitigation actions.

This is a new effort on the part of Québec’s universities to begin to take seriously their responsibilities towards the students they are entrusted to care for. You may remember that I wrote a long article, “No student should be denied a climate education,” on September 15. I strongly urge all levels of educational institutions to speed up and intensify their commitment, and let’s not ever forget the need to robustly put into general practice a weaving of biodiversity into the heart of education. In order to register for the webinars, see https://unis-climat.teluq.ca

“Let not any one pacify his conscience by the delusion that he can do no harm if he takes no part, and forms no opinion. Bad men need nothing more to compass their ends, than that good men should look on and do nothing!”

John Stuart Mill, inaugural address delivered to the University of St Andrews on February 1, 1867

A generous and just Thanksgiving: doing more than voicing gratitude for the Earth’s bounty

“Acknowledging traditional territory specifically focuses on First Nations land title and rights, but it is also a means of raising a broader awareness of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit culture and history – specifically by way of our own relationships to the land and water… It is impossible to talk about Indigenous-specific anti-racism without talking about European imperialism and the theft of land…The story of First Nations people in Canada is…through the relationship to the land and water.”

First Nations Health Authority

The loss of biodiversity and the climate crisis are intricately enmeshed with colonialism and its malevolent kin, capitalism. The destruction of Indigenous cultures and of their ability to be stewards of the Earth continues to be felt acutely today. Although it is blatantly insufficient as a token event to refuse to celebrate colonialist Columbus Day in the U.S. and to include Indigenous Peoples Day in Canada’s Thanksgiving holiday meditations, we can come closer to embracing Indigenous Earth stewardship. Actions are needed to dismantle and sink the toxic imperialist legacy of Columbus’s ship. Please listen to the podcast Holding the Fire.

Annie Proulx’s book Barkskins tells the multi-century story of the deep divide between the spiritual and ecological consciousness of Indigenous peoples and the genocidal policies of European invaders who destroyed the Indigenous peoples’ culture in tandem with the creeping deforestation of incredibly biodiverse lands, and the pollution of the waterways in New France (Québec), is well documented. And Serge Bouchard’s The Laughing People: A Tribute to my Innu Friends speaks poignantly of the invasion of Indigenous lands. Both books are available at the Lennoxville Library. The effects of this ecocide can be seen all across Southern Québec and into the North as well.

Of course it has been de rigueur for some years to murmur or pen in a sombre and contrite tone, with almost religious fervour, references to Indigenous unceded territory by institutions such as universities, churches, corporations and governments at the beginning of a lecture. Equally reprehensible are articles, sometimes written by lawyers, that endeavour to give credibility to their weak arguments by surreptitiously placating or distracting, or perhaps feebly attempting to assuage the conscience of white audiences by parroting the undisputed fact that lands have been stolen (‘unceded territories’) from Indigenous peoples; by some, it is implied as a consequence that we have forthwith absolved ourselves by faux confession and can now blithely continue on with the show. How unctuous and hypocritical. And indeed, it shows how ethically bankrupt we are when we bare our chests with humility to proclaim our genocidal past and continuous ecological theft… and stride on, as is implied in the First Nations booklet. Let’s be clear: acknowledging unceded territory is only a first step aimed at a reconciliation that must go on to weave actions into tangible and ultimately mutual resolution.

Many might ask themselves, upon coming to a lecture and hearing a prescribed and rote 30-second acknowledgement of the occupation of unceded territory, whether audiences should rise to their feet and scream, “Give the land back! It is never too late. Give back this sacred land to the rightful peoples who honour it!” I for one can feel the audience squirm in their seats each time words are uttered but are divorced from positive actions. What would happen if they did stand up and demand restitution? Most lawyers who represent these institutions and who only uphold and pass on the colonialist mantle would surely refuse, and if flush with money might perhaps hand over with much fanfare a building or two to parade their generously to the vanquished on their unceded territory in order to ‘compensate’ a grotesque injustice.

Historically, to pillage the land in the name of an unknown future is the invader’s raison d’être for most solutions, is even called ‘sustainable development’ by some so-called experts, and is the antithesis of Indigenous peoples’ close connection to the Earth. I recently read one article that mentioned sustainability 20 times. The current invasion of Indigenous lands in British Columbia for the construction of a fossil fuel pipeline is only one of many instances whereby ecocide, tragically fostered by governments and institutions as a pseudo-policy for ‘energy security’, manifests itself, and in Québec there is no shortage of examples.

Done with the equivalence and finesse of a slaughterhouse knife that effectually pars down the existence of biodiverse lands into a newly ‘enhanced’ achievement is something that has always been emulated by corps of engineers throughout the world, and Québec is no different. It’s called ‘expertise’.

It’s time to radically build on and revitalize past Indigenous acknowledgements in our communities that have sadly been reduced by bad faith in some instances and to vigorously take on non-hypocritical action by returning lands to Indigenous peoples. For example, if you are an institution that occupies 100 acres on Indigenous unceded land but have much more land than that, give back the majority of that land. All the rest is a capitalist investment supplanting wisdom by rapacious greed. “As he cut, the wildness of the world receded, the vast invisible web of filaments that connected human life to animals, trees to flesh and bones to grass shivered as each tree fell and one by one the web strands snapped.” ― Annie Proulx, Barkskins

There are of course those who speak with deep humility and truthfulness when they acknowledge Indigenous lands, as it is clearly not their intention to spout words of acknowledgement regarding unceded lands before a church service or a university lecture in the manner that is criticized in the First Nations Health Authority booklet cited in this article. Crucially, what actions will be taken to truly allow for reconciliation and justice? Shredding a landscape, ripping off its topsoil, polluting the land with noise and diesel contamination and then moulding and reformulating the topography like a science experiment is NOT the way to acknowledge unceded lands. This is the festering sore, the long cut road through primeval sacred forests, which started 400 years ago.

There are many people who unreservedly understand the climate and biodiversity crises. The September 29 Climate Action protest in Sherbrooke brought out maybe 300 people, and even though some free bus tickets were distributed, the publicity was at best incomplete and few students attended from Bishop’s and University of Sherbrooke. Most of the protesters were exuberant teenagers, together with a new group of older people who have banded together to fight climate/biodiversity collapse, but there was only a smattering of university students. After a summer of great catastrophe around the world, including the forest fires of Québec that caused so much destruction and pollution, would not more young people be expected to come out? Could not teachers have announced in each class the climate protest and urged their students to attend by creating communities that care? Is that not one part of climate education? Government and educational administrations worldwide, in thrall to climate deniers for 35 years, refused to educate their youth, and now unenfranchised, under-educated and a mostly consumer-obsessed apolitical students populate the campuses of many Canadian universities, with few skills to protect their future. Have adults adequately provided young people with the guidance and straightforward universal science education necessary to counter these crises? Clearly not.

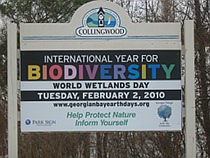

And yet, when I attended a three-hour biodiversity workshop last week, I witnessed a strong resolve on the part of people younger than 35 to move past the slumber, the inertia of older self-complacent generations. Desperate to slake their thirst for knowledge, they seek it outside the bounds of the institutions upon which it is incumbent to provide education in the most pressing issues of our time.