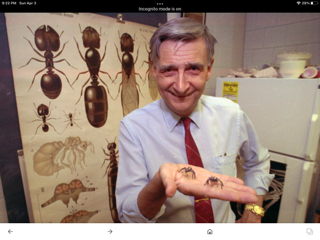

The man who loved ants

A tribute to a great naturalist: E.O. Wilson

“The most successful scientist thinks like a poet—wide-ranging, sometimes fantastical—and works like a bookkeeper.”

E.O. Wilson

“Unless we move quickly to protect global biodiversity, we will soon lose most of the species composing life on Earth.”

E.O. Wilson

When the preeminent American scientist Edward Osborne Wilson died in December last year at the age of 92, the world lost not only one of the greatest naturalists of the last 70 years, but a man who was so much more than a scientist. Wilson was a myrmecologist, one who studies ants, and he was even nicknamed Ant Man. Famously, he discovered how many insects communicate through the production of chemicals called pheromones.

I have read many of Wilson’s books. His breadth of knowledge was astounding, and that is why I was drawn to his remarkable pursuits. Books with names such as The Meaning of Human Existence, On Human Nature, The Diversity of Life and The Social Conquest of Earth tell us that Wilson was a man who pondered huge ideas. Was he the foremost expert on ants? Yes, but as the most prominent evolutionary biologist of the last century—he has often been called “the heir to Darwin”—he explored a vast array of potentially controversial subjects throughout his life and loved the challenges associated with these monumental projects.

One of Wilson’s controversial theories was sociobiology, which he explained as “the systematic study of the biological basis of all forms of social behavior in all organisms.” Many prominent scientists thought it was outrageous to say that altruism, for example, could have evolved through natural selection. Evolution through natural selection was thought to foster only physical and possibly behavioural traits, but Wilson thought this theory did not delve far enough into the multi-dimensional raison d’être that a portrait of the complete human needs to explore—and not just humans, he was quick to say.

It is unusual for any scientist to have such a profound influence on the course of so many areas of knowledge, and Wilson relished bringing the humanities and science together to solve our greatest problems. He has been one of the most vocal proponents of bringing together the unity of knowledge. It was his view that the cultural significance of the humanities was critical for there to be an expansive understanding of who we are, and that when scientists team up with the humanities to solve our most far-reaching concerns and aspirations, humanity will come together. “It is within the power of the humanities and the serious creative arts within them to express our existence in ways that begin to realize the dreams of the Enlightenment,” he wrote. He liked to imagine that extraterrestrial beings, upon coming to Earth, would not be interested in our technology or science but rather would be fascinated by the art, music, literature and other fields in the humanities that make us unique.

Like Darwin, whom he called the greatest scientist in history, Wilson was not only a driven discoverer of previously unnamed species. He also wished passionately to try to answer the big questions that related to human existence. “Where did we come from, what are we, and where are we going?” was a prevailing mantra of his. His life’s work was, James D. Watson (co-author of the academic paper proposing the double-helix structure of the DNA molecule) stated, “a monumental exploration of the biological origins of the human condition.” As a result, Wilson frequently met opposition from other scientists. He had this to say, in his Letters to a Young Scientist, about perseverance: “You are capable of more than you know. Choose a goal that seems right for you and strive to be the best, however hard the path. Aim high. Behave honorably. Prepare to be alone at times, and to endure failure. Persist! The world needs all you can give.” And persist he did!

Throughout his long career Wilson reached out to young people and tried to inculcate a close connection with Nature. His famous bioblitzes would involve many students, who would go out with him for an afternoon or for 24 hours to a city park or a wilderness and catch insects and other creatures to identify. His enthusiasm was contagious and his nonstop efforts were sometimes described as childlike. “For the naturalist, every entrance into a wild environment rekindles an excitement that is childlike in spontaneity, often tinged with apprehension,” he wrote in his 2002 book, The Future of Life. Such experiences, he insisted, remind us of “the way life ought to be lived, all the time.”

Children accompanied Wilson in his exploration of Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique (and you can see a wonderful video of their bioblitz at https://tinyurl.com/eowilson-bioblitz), but his visit there was also a cautionary tale for us. Here was an incredibly biological diverse place that had been partially destroyed by war and greed. “Destroying rainforest for economic gain is like burning a Renaissance painting to cook a meal,” he had emphasized. The purpose of the visit was to find out if Gorongosa could be restored to its previous natural glory (https://tinyurl.com/eowilson-gorongosa). The E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Laboratory has become a huge success in bringing together a diverse group of local and international enthusiasts to rejuvenate Gorongosa. (In recent years national parks have come under scrutiny because of their blatant disregard for local participation and, even worse, the forced removal of local human populations from newly formed parks.) “Humankind will ultimately awaken to its responsibility to the Earth,” Wilson maintained. In fact, he has emphasized throughout his writings that it will be a common ethics that will be the ultimate driver to protect the planet; we will not succeed otherwise.

Wilson called himself an agnostic and declared: “The true cause of hatred and violence is faith versus faith, an outward expression of the ancient instinct of tribalism.” And although he welcomed the role of religions in helping to save the planet, he insisted that “the best way to live in this real world is to free ourselves of demons and tribal gods.”

I believe that Wilson’s finest contribution to biology and our world was his steadfast resolve to push forward conservation biology. He was justifiably called “the father of biodiversity.” His very readable short books Biophilia and The Creation lovingly describe our planet’s living world—and indeed the word “biophilia” means “love of biological life”—but he admonished us, saying that a legacy of inaction to protect the diversity of life on Earth will catastrophically push us into the Eremocene, the Age of Loneliness, following the disappearance of millions of species.

Wilson believed in the power of education, and his proposal for an Encyclopedia of Life led to the creation of an expanding global online database (https://eol.org) to include information on the 1.9 million species we know of. (There may be as many as 10 million species on Earth.) He was deeply alarmed at the acceleration of species extinctions around the world. In 2016 his book Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life was published, and he worked tirelessly to promote the Half-Earth Project (https://www.half-earthproject.org), a call to protect half the land and sea on Earth in order to manage sufficient habitat to reverse the species extinction crisis and ensure the long-term health of our planet.

In 2016 ornithologists discovered a previously unknown ant-eating bird in Peru. Everyone agreed that it should be named after Wilson for his unparalleled work in conservation. The Latin name for this bird is Myrmoderus eowilsoni.

Edward O. Wilson will be mourned by millions and his books will continue to inspire us to be closer to this Earth and our responsibility to protect it.