Giving young people a public voice: a conversation with Georgia LaPierre.

Tell our readers about yourself, Georgia. Has your family background encouraged you to be interested in social justice and climate/biodiversity issues or in general to have an appreciation for the natural world?

I am 21 years old and grew up in Montreal. My family, particularly my dad, encouraged me and introduced me into the world of social justice and ecological issues by bringing me to protests and courses/talks about Nature and our changing climate. I don’t think I would be as socially aware and as involved in the climate justice movement as I am today if it weren’t for their support.

A recent article in the scientific journal Nature looked into the emotional impact and the impaired trust in government the climate crisis is having on young adults.

Having read that article, do you identify with any of the concerns that were expressed by the 10,000 people who were part of the survey?

Of course I identify with the youth who answered this survey. I would find it quite worrisome if there were youth in our world today who weren’t suffering from climate anxiety. The science is clear – we have a very limited time frame to reduce the impacts of climate change, and our governments are doing nothing to act effectively. This makes me, as a young person, angry and sad. It makes it seem that they simply do not care about us. I go through phases where I’m a glass-half-full or glass-half-empty kind of person when it comes to the climate crisis. When I lived in Montreal, I went to the Fridays For Future protests every week, and the government made no response to our efforts. It is clear that they are not taking our demands and our futures seriously. If the government truly did care about their youth (who are alive today) they would not sign on for new pipelines and fracking contracts. They would take effective change that climate scientists are suggesting.

What courses are you taking at Bishop’s University? What made you choose those classes?

My major is sociology with a concentration in gender, diversity and equity with a minor in Indigenous studies. All my classes have to do with these topics. I picked this major because, since high school, I’ve been a climate and social justice activist. I take the term intersectionality to heart – all issues in our world caused by human and capitalist activity are related, and they must be tackled as a whole in order to effect meaningful change. The courses I am taking make me understand our society better and these issues better. Using this academic knowledge, I hope to help make a change.

Do you participate in outdoor activities such as snowshoeing or walking?

I do! Since a young age I have hiked, skied, walked and been on canoe trips. Without these activities, I would not have the relationship I do to Nature today, and probably would not strive as much to save it. Participating in outdoor activities showed me the beauty and importance of Nature, and made me understand that I am a part of it. I believe everyone should take time to be in Nature, because without it we are lost.

Have you ever experienced taking a wilderness camping trip? If so, what impact did it have on your sense of belonging in Nature?

Yes! I would go on canoe trips, up to 5 days, and often we would be the only ones on the lakes and the rivers. My connection to Nature and my love for Nature was born out of these trips. I felt like I was a part of the current and the forests. On these trips, Nature made the decisions for us, so if there was thunder we could not continue our day and would have to make up for the lost kilometers on the following days. I learnt more about Nature after this, which brought me towards activism when I learnt of the devastating effects human activity has on it.

Are you deeply connected to Nature, or do you sense that you’re somewhat alienated from it?

I would argue that I am deeply connected to it. However, I do get lost from it sometimes. I’ll be so busy with work and school and social life that I’ll realize I haven’t spent enough time with/in Nature. My friends feel the same way. We should have to make time for Nature in order to feel a part of it. We should always feel a connection to it.

Do you believe in your generation’s ability to weather the intensifying biodiversity and climate uncertainties? Are you hopeful?

I think in my current state I have been pessimistic. I believe my generation wants to effect change, but the science is clear: the change needs to come now. I’m tired of political leaders telling us how inspiring we are and how we’re the generation who will make change. Right now, we are all asking them to change, and they just don’t. I believe older generations need to take us seriously now rather than tell us we’ll change the world when we’re in positions of power.

Is it important for people to respond politically to the climate crisis, or are there other ways that can make a difference in order to protect the planet?

I think responding politically is very important, I think using your right to vote and voting for who you think is best suited to run our country and save the world is very important, but I do also think that there are other ways you can create change. I think through academia (what I’m planning on doing) we can help find the solutions to the climate crisis. I think through art you can convey the feeling of your generation into a digestible piece of art. I think by being a farmer and turning away from corporate farming to local, sustainable farming you can make a difference. There are so many ways that individuals can move towards making a difference, but until the government begins to take action, nothing will get better, so vote!

What do you do to lessen your daily impact on the Earth?

I am vegan and have been for about two years. I have reduced my consumption, I rarely buy clothes first-hand and I am aware of the packaging I buy food in. I also have decided not to travel by flight until I have discovered the world around me that is reachable by train or car. I really do believe in individuals reducing their carbon footprint – I think it helps us feel a little less anxious and helpless. Yet I would like to reiterate that individual action is not enough. Corporations are the ones who pollute the most, so when governments and organizations ask you to use reusable straws they are taking your attention away from the actual issue at hand.

Are you optimistic for the future? Do you wish to have children one day?

I am not optimistic. It has been a couple of years since the first very serious IPCC report came out, and nothing has changed. Even the things that have been promised are happening too late to make a difference. I do not wish to have children. I did when I was younger, but due to the climate crisis I can’t bring children into this world. I think that as a parent your number one job is to love your child unconditionally, and I decided to not have children as a part of that love, because they would never be able to live up to their full potential or follow their dreams. However, if someone plans on having children, I completely support their decision and encourage it. This is just my personal opinion.

Have you spoken in some depth to other people in their late teens or early twenties about the climate crisis and how you might stand together and fight for your future?

I have! And I have gotten two responses: one is very optimistic and turns towards making effective change locally and globally, and the other is simply asking, “But what can be done?” I have never found an in-between sort of answer. I think there is a large disconnect between these two types of youth, and I would like to find a way to bridge the gap and create a stronger sense of urgency in those who don’t want to change or don’t see how they can help.

Do you sense that your generation is different compared to older generations in its approach to tackling climate concerns?

I believe it is. I think many youth in my generation are turning away from the capitalist system. I believe that we have begun to understand that exponential growth does not work in harmony with Nature and that we need to turn towards a system that not only coexists with but is a part of Nature, rather than a system that actively works against it.

Do you belong to any activist groups? Do you go to protests?

Yes! In Montreal I was involved with Dawson Green Earth, Fridays For Future and Extinction Rebellion. And, yes, I went to a lot of protests. In my last year of cegep I went to at least one protest a week. I think that showing your discontent is one great way to demand change from the government.

On campus at Bishop’s it’s a little harder, so I’ve been focusing on more local change. I am junior co-chair of the Sexual Culture Committee on campus, for example, and we organize a yearly march called Take Back the Night and work on projects to create a safer and healthier environment on our campus and in our local community.

What plans do you have for the future, after graduating from Bishop’s?

I have a couple of plans, one of which is becoming a professor and doing research. The other is to work for organizations and advocate for a more just world. I will see where the wind takes me, as they say, but one thing’s for sure: activism has been a part of my life from a very young age and I think it will always be a part of my life.

A review of Carl Safina’s Becoming Wild

As a human being, one has been endowed with just enough intelligence to be able to see clearly how utterly inadequate that intelligence is when confronted with what exists.

Albert Einstein

There is no folly of the beasts of the earth which is not infinitely outdone by the madness of men.

Herman Melville, Moby Dick

Carl Safina’s Becoming Wild: how animal cultures raise families, create beauty and achieve peace is an intimate tapestry of the lives of three animals that exhibit meaningful cultures. Sperm whales, macaw parrots and the chimpanzees are visited, and with the help of scientists and naturalists, Carl Safina examines their families in the context of culture. What makes these animals who they are? For example, sperm whales have complex communications that allow extended families to stay together. A certain group or ‘clan’ of these whales will only communicate with the same members of that clan. Water is an incredible conduit for sound and as the whale moves across the oceans a whale can listen to and respond to another member many kilometres away. This also enables them to come to the defence of the young extremely quickly.

But how they come to the defence of their young is determined by learning specific to that group of whales. “Genes determine what can be learned, what we might do. Culture determines what is learned, how we do things…Social learning is special. Social learning gives you information stored in the brains of other individuals. You’re born with genes from just two parents; you can learn what whole generations have figured out. “ Culture presupposes that there is innovation in a group. The author gives us many examples of how just one animal can impart to others a new way of interaction in the world. So there is both the process of learning and conformity. Carl Safina goes on to define culture as “information that flowssocially and can be learned, retained and shared…Innovation is to culture what mutation is to genes; it’s the only way to make any process, the root of all change.” Becoming Wild is all about the amazing cultures found in Nature, not just human culture. Tragically, humans until recently thought they were the only beings on the planet that had culture. Roger Payne’s 1970 recording of the whales ignited a keen interest in other species. When Payne and Scott McVay published “Songs of Humpback Whales in Science in 1971 everything changed, well almost everything, except the continuation of the industrial killing of the great whales. People began to strongly question the need to destroy these sentient creatures. Was it imperative that margarine contained whale oil, for fertilizer or that machinery needed their oil?

It has always struck me that one of the great perversities perpetrated by fossil fuel corporations and their lobbyists is its active and unremitting ability to help kill off whales, something that men in boats throwing harpoons could never quite manage. You’d be correct in assuming that once whales were not murdering for their oil to light up houses because fossil fuels took over that task things would have improved. As the oceans lost large numbers of whales the boats had to go further and further. The cost in fossil oils became almost prohibitive but that only pleases the petroleum industry. When whaling vessels have to go to Antarctica to hunt that makes the oil executive richer. This is not to say that the petroleum industry pushed the hunters to destroy the whales, but it is part of a web of deceit and greed that has brought us to our ecological crisis. Carl Safina puts it succinctly: “Energy is always a moral matter. It has tended to reward immoral behaviour.”

What kept the butchery going was the ‘respectable’ quasi-scientific but highly political International Whaling Commission that was established in 1946. Unbelievably the Commission was set up to stop the extermination of whales so commercial whaling could continue! Quotas were arbitrarily established and then countries lied about their catches. A moratorium in 1979 came and went. Only public opinion saved the whales…or did it? Each of Safina’s chapters on whales are entitled ‘Families’. We learn about the close knit life of the whales and how unique each family is. All the members in a group of families ,a clan, use ‘codas’ that identity them specifically. Codas are clicking sounds that have specific meanings. Each family has its own unique series of clicks that give information. New skills to hunt fish are shared in the clan. Whale cultures teach the young not only how to survive but to learn their way of life. When adults are killed by humans in grotesque numbers, the adolescents have not yet been given the opportunity to have passed on to them life skills. Genes are not enough to survive. Fragmentation of families destroy the abilities to be innovative. If “culture is home” as the author describes it, whales lose their homes when families are torn apart. Carl Safina reluctantly says, “It means something acutely awful, I think: that the human species has made itself incompatible with the rest of Life on Earth.” To say this is to send a jolt of horror through the reader. Whales have responded to the question, “How best can we live where we are?” Will humans do the same?

To this day the Japanese still demand that whales are slaughtered for ‘research’. Arguing that whales are killing too many fish brings to mind the same spurious rant that wolves must be decimated to save the livestock industry, and to bring it closer to our human ‘home’, when indigenous groups lose their languages and land all is lost.

Scientists now know that sperm whales help the oceans to be a healthy enriching habitat for so many species. They are also a key species to slow down the climate crisis. When these whales dive, guided by sonar, into the great depths they capture great volumes of squid. They bring to the surface many nutrients, but just as importantly, the whales poop usually before they dive and it becomes an important source of nutrients for wildlife and the propagation of plankton that soak up the carbon dioxide.

Recently, a lot of effort has been brought forth to celebrate the lives of animals. David Attenborough’s documentaries and others such as “My Octopus Teacher all are trying to undo the self imposed calamity humans find themselves in; Becoming Wild does the same.

Whales are not alone in bringing a culture to their communities. Macaws and chimpanzees do the same. Safina writes: “Flexibility that becomes shared habit is called ‘custom.’ Customs learned through generations becomes tradition. Traditions make up culture… A culture can be a package of traditions, a repertoire of behaviours, skills, and tools characterizing a group in a place.” We humans can easily recognize our own cultures even if their everydayness is sometimes hidden from us, but once in a while innovation moves that culture to a new, enriched place. Conformity and nonconformity are equally vital in shaping a culture. But why can’t we accept that non-humans also have cultures? Becoming Wild is as much a contemplation and celebration of the cultures of three non-human species as it is of the human one, but Safina also speaks forcefully about the frailties that undermine human potential.

Safina’s chapters on the marvellous cultures of macaws and chimpanzees are also a conversation about who we are. He asks us to pose and try to answer difficult questions. Our obsession with violence is mirrored in that of chimpanzees. Why have our cultures allowed this to happen? Humans also place great value on beauty and on peace, so why haven’t we been able to supplant violence? It’s not that chimpanzees and humans don’t harbour “tender emphatic concerns for others and brave altruism.” We do, but both species are trapped in hierarchy and male, misplaced violence. “Chimps don’t create a safe space; they create a stressful, tension-bound, politically encumbered social world for them to inhabit. Which is what we do. This behavioural package exists only in chimpanzees and humans… Chimps may hold clues to the genesis of human irrationality, group hysteria, and political strongmen.” It appears to be abundantly clear that another primate, the bonobo, has it right when their cultures (of which there are many) are based in matriarchal supremacy, as peace reigns in those communities.

The author brings us to a research station on Peru’s Tambopata River where various species of macaw are studied. Here, too, are vibrant cultures that celebrate life. Safina wants to comprehend the nurturing place that beauty plays in the lives of these birds. He also wants to understand why beauty is so important for humans. His answer, at the end of the book, is succinct: “Living things anchor what is beautiful… Beauty is a simple crib-note for all that matters.” An astonishing response, I thought, and though seemingly esoteric, I believe that it makes perfect sense. Unlike the smaller green parrots, macaws are fabulously colourful, and even though they are strikingly beautiful and so visible there are few predators that can catch them. Their high level of intelligence has given them the means to avoid being eaten. Beauty is their reward. Safina harks back to Charles Darwin when he speaks about sexual selection and beauty. Beautiful males are chosen by females: it’s that simple. Safina takes up this idea: “Beauty—for the sake of beauty alone—is a powerful, fundamental, evolutionary force… The radical preference of Life is: beauty.”

In the Budongo Forest in Uganda Safina meets Cat Hobaiter, who has been observing some chimpanzee communities for over a decade. We learn about the lives of several chimps and their interactions within their groups. There is an astounding similarity between their gestures and those of young human children. Most are identical and have similar meanings. Human children use 52 distinct gestures, and chimps use 46 of those same ones. Gestures create the means for cohesion within the family, and greater tenderness, particularly between mother and baby. The chimp mother is the sole parent to bring up the babies, and peace resides there. Between males, and certainly in the complicated relationships the alpha male has with other males, violence is often ready to surface. Contrast this with bonobos’ path to peace: “little violence among males, between sexes, and among communities.”

Throughout the book there is a deep uncertainty that humans will have the courage and capacity to see that non-humans must be cherished and protected. Safina asserts that “caring that they’ll exist after we are gone is a moral matter… The things that threaten whole communities of other species also threaten us… Africa keeps the deepest of primate pasts. The question is whether it holds a future.”

Only humans can now answer that. Carl Safina’s tribute to whales, chimpanzees and macaws can empower us to embody a new ethic for this world: one that loves all life on Earth, not solely our individual tribes’ wellbeing.

Suffragettes’ “Deeds, not words” motto invigorates climate activists

“Where the voice that is in us makes a true response,

Where the voice that is great within us rises up,

As we stand gazing at the rounded moon.”

(Wallace Stevens)

You may be surprised to learn that if you look at the origins of the word “human” you’ll discover that, a long way back, it is related to the word “humus,” meaning earth or soil. Humus is the organic component of soil. To be human is to be from the soil, and right now there are millions of conversations taking place that strive to bring us back to being a “people of the earth” as our ancestors knew deeply within their beings. These conversations are not only between humans. As we discover the “secret lives of…” all sorts of species, hugging a tree might not be considered so bizarre to many. Industrial society wished to stamp out our love for Nature; now it is simply resurfacing. Just ask a cat, horse or dog person if they converse with those animals, for example. But is humanity living up to its own name, people of the soil?

Many climate and biodiversity campaigners, including Extinction Rebellion (XR), Greenpeace and 350.org, are strongly critical of governments’ climate inaction. These same groups denounce fossil fuel reduction targets of 2050 – or any other year beyond 2030 – as being truly the “new denial” by corporations and governments who refuse to accept the climate/ecological crisis. Activists point out that politicians looking only towards the next election couldn’t care less about what happens in 2030 or 2060, and that is why campaigners are taking up the suffragettes’ clarion call “Deeds, not words.”

When on Earth Day this year, after nine women in the UK smashed 19 windows of the headquarters of a major bank, a journalist asked a member of XR if the public would not call that vandalism, her response was that no life was ever endangered by the broken glass, but that since 2015 that bank has supported the fossil fuel industry with tens of billions of dollars – it should be noted that Canada’s RBC does the same – ignoring the plain truth that this is financing climate breakdown. It is the banks that are the true vandals – of the planet’s integrity. Who, she enquired, is really the criminal?

The same stunts corporations use by publishing targets and long-term goals to show off their climate care could be found at the climate summit hosted by Joe Biden on Earth Day. Brazil’s climate-denying president, Jair Bolsonaro, gave us little to believe in concerning his intentions for the wellbeing of the Amazon, by cutting the budget of his environment ministry despite his promise to stop all illegal deforestation by 2030. The UK prime minister, Boris Johnson, utters the same hot air on commitments to real deeds to stop runaway climate change. Biden appears to be one of the few politicians in America who are taking bold steps to move forward on climate issues after four disastrous years of Trump climate denial; but will a recalcitrant congress let him proceed? (Trump and the Republicans were co-perpetrators in the race to commit ecological catastrophes.) As usual, Trudeau is giving the same mixed messages to Canadians. He has clearly emerged as one more superficial wafting and ineffective politician.

The International Energy Agency confirms the fact that fossil fuel use will increase in 2021, undermining various targets of the rich nations. Fatih Birol, the agency’s executive director and a leading authority on energy and climate, said: “This is shocking and very disturbing. On the one hand, governments today are saying climate change is their priority. But on the other hand, we are seeing the second biggest emissions rise in history. It is really disappointing.”

It is because of the historical intransigence of world governments and corporations that the Glasgow Agreement between worldwide non-governmental organizations and peoples is now finding ways to demand climate justice before and after the UN Climate Summit that is to be held in Glasgow this autumn. www.glasgowagreement.net/en/

Acclaimed eco-philosopher Joanna Macy explores through her many books, interviews and actions our relationship with Earth’s beings and what we must do to revitalize our commitment to saving ourselves and all life on Earth. She warns us, saying, “Of all the dangers we face, from climate chaos to nuclear war, none is so great as the deadening of our response.” She speaks with great urgency when she discusses the “Great Unraveling” now taking place as species are driven to extinction. Yet she encourages “active hope,” the realization that the actions to save our ourselves and the planet are always there for us, regardless of the current state of planetary demise, “as people acting in the defence of life wake up to the grandeur of who they are and find sources of strength and synergies beyond what they could have expected.” This is the Great Turning that she sees growing rapidly throughout the world.

Macy asks herself and us difficult but vital questions that need to be addressed if we are to stop the destruction, the unraveling of our planet’s ecological stability. “How do we be fully present to our world at a time when the suffering and the future prospects for conscious life forms are so grim? How do we look straight in the face of our time, which is the biggest gift we can give, to be present to our time? It’s so tempting to want to just pull back like a turtle in its shell. It’s so tempting to just close your eyes and busy yourself with other things.” Her thinking encompasses Buddhist teaching regarding the universal condition of suffering present in the world. She is convinced that apathy is the “refusal or inability to suffer.” She goes on to say that we can choose to be with our world with our minds and hearts present to the suffering that is there.

The Great Turning can start by slowing down the destruction of corporate growth and individual overconsumption. New patterns of collective behaviour, new ways of construing our relationships on every level can evolve, so the first dimension of the Great Turning is “Holding Actions” and slowing down the unravelling of our world through many kinds of activity that, for example, welcome regulatory and legislative work, and protests on the streets that lessen the harm being done, including everyday “slow violence.” Direct action is important, but it is only one path to be taken. “Sustainable Structures” is the second dimension of the Great Turning and might include new ways to create an ecological agriculture/permaculture, new ways of measuring wealth and prosperity, or invigorating communities with true resilience. The third dimension is “Shift in Consciousness”, rooted in our perceptions of reality. Macy calls this a “cognitive revolution,” which is the recognition that our planet is a living system, not just a warehouse or sewer to be despoiled. She goes on to say that this revolution is a shift from seeing the world as stuff, things and entities to seeing reality as “flows of relationships” that are able to be self-regulating and evolve in time to flourish with extraordinary complexity and intelligence. All three dimensions are able to reinforce each other and there isn’t just one way for the Great Turning to proceed. Joanna Macy’s memoir, Widening Circles, is available at the Lennoxville library. www.joannamacy.net

Recently I attended a virtual talk given by Addy Fern. She and her husband, Ken, have transformed a 28-acre barley field in Cornwall, UK into a biodiversity-rich gem. What I witnessed when I visited Plants for a Future some years ago and again last week was Addy’s passionate desire to participate in this Great Turning. What was most striking to see was an aerial photo showing an oasis of dense woodland in the middle of a depleted landscape. Sadly, Addy’s commitment with her family and volunteers to transforming a monoculture on poor soil into an amazing place vibrant with Nature has had little influence so far on the surrounding area. I asked her whether the neighbouring farmers had been inspired to follow her family’s 30-year lead in nourishing the land. Did they not see what a high level of health Plants for a Future was giving to all of Nature there? There are no real answers to these questions except that a change of consciousness needs time to manifest itself, and there is no doubt that the Ferns’ work is one of many seeds across the planet that are participating in blooming the Earth. www.theferns.info

A few miles from Lennoxville lies La Généreuse organic farm. Here the family of Francine Lemay have likewise created a place that celebrates Nature. The last 40 years has seen many transformations to the land. They have always stayed true to biodynamic principles when growing food, and the accompanying forest encourages wildlife. The large field with a variety of decades-old apple trees has never been sprayed with pesticides, and the bee colonies nearby help with pollination. La Généreuse also encourages the arts and early education. It is truly a place of wellbeing, supporting the ecological self to flourish. www.lagenereuse.com

Homer-Dixons book, Commanding Hope, brings us to a better future.

We…must come to terms with nature, and I think were challenged as mankind has never been challenged before to prove our maturity and mastery, not of nature, but of ourselves. – Rachel Carson, author of Silent Spring

In the past the December holiday season and the coming New Year imbued many of us with a vision of a prosperous and loving future. For most of us the pandemic has been an unmitigated disaster: people we love have died, how we work, learn and communicate has been severely hampered, daily comfortable schedules have been uprooted, financial woes have been exacerbated, our mental health has suffered through unprecedented isolation, and our sense of overall security in a world we thought we could have some control over has been smashed. Those who could choose to take cruises and planes at a moments notice have found themselves sitting at home. Even moneys perceived ability to fix any problem will not loosen the grip of this virus. A cure-all vaccine is trumpeted, but it seems that many people will refuse it, questioning its efficacy and the motives of governments and the pharmaceutical companies that produced it; some even speak of dark and tyrannical objectives. Fear and trepidation permeate our daily lives.

At last humans are realising that we are part of Nature, which we have abused for so long. But is this reluctant and grudging acknowledgement coming too late for us? Our ever-increasing encroachment into natural habitats and refusal to respect the notion of limits to growth for humanity, characterized by global unethical capitalism run amuck, is now in the process of ruthlessly pursuing climate breakdown. Covid-19, it appears, represents one more landmark on the road to devastation that we collectively continue to encourage.

Thomas Homer-Dixons recently published book, Commanding Hope: The Power We Have to Renew a World in Peril, comes at a time when many people believe humanity is soon to be forced to its knees. But Homer-Dixon states: Real social and political change only happens in times of crisis, because crisis is needed to discredit existing systems of worldviews, institutions, and technologies, and the structures of power that sustain them.

Commanding Hope is dedicated to Homer-Dixons two young children, Ben and Kate, who are continually alluded to throughout the book, whether that be in a drawing of theirs or in dialogue between them and their father and mother. To put it succinctly, Homer-Dixon wrote this book as if his childrens lives depended upon it. It took him eight years, and nothing will stop him from finding a non-magical elixir of knowledge and informed action to save his children and ours.

He begins with an account of the heroic efforts of Stephanie May, a young Connecticut woman, making phone calls in 1957 asking people to protest against atmospheric nuclear testing. In 1961 she goes on hunger strike while walking up and down in front of the Soviet Unions Manhattan UN mission, asking them to save the worlds children by eliminating the tests. To her amazement the press takes notice and ultimately her efforts bear fruit. Against the odds, the powerful determination that she displays is in its essence what Homer-Dixon calls commanding hope. And this is the same engaging hope that teenage climate activist Greta Thunberg displayed in 2018 when she sat outside the Swedish parliament with a handwritten sign.

Homer-Dixon contrasts this positive renewal of the world with the Mad Max apocalyptic films, where the world is drawn down to the lowest ecological and civil possibilities. But juxtaposed with that nightmare he discusses J.R.R. Tolkiens Lord of the Rings and the unlikely push by the communities of Middle-Earth to forge again lost alliances that will bring about a cessation of grotesque hostilities and a renewal and affirmation of an alternative worldview that cherishes life and happiness. The long quest to find a way to finally dispose of the Ring and bring about an era of peace and harmony finds its greatest strength in an unassailable sense of hope; it is a hope to create a better world around which Homer-Dixon weaves his book. We recall all the tribulations and faltering ambitions to create a just society in The Lord of the Rings, and Homer-Dixon reminds us that our present-day world far exceeds the dangers expressed in Tolkiens book. Humanitys struggle to stop climate chaos, an ecological catastrophe, nuclear destruction and the rise of authoritarianism constitutes an almost impossible task compared to the ascent of Mount Doom, a goal for the Fellowship of Middle-Earth that will become achievable, if immensely difficult. Homer-Dixon calls it a superordinate goalone thats clear and specific, that everyone shares, that overrides all others, and that cant be achieved without cooperation, and he repeatedly cautions us that we might not be so fortunate but we have too much at stake not to vigorously pursue safety for our children.

True, our challenges far outweigh Frodos, but Homer-Dixon affirms that we can push back the darkest elements of humanity and flourish. But how do we get there? By intensely reviewing and modifying our personal and public worldviews as well as understanding that our institutions and technologies are tightly interdependent: they influence each other, depend on each other, and usually hang together in a cohesive way. Stereotypically a western worldview might include a commitment to personal freedom and free enterprise, while its institutions support free economic markets and a communitys rules, and its technologies let us feel were independent by, for example, driving cars. Homer-Dixon strongly recommends that we immediately set about transforming our mindsets and ultimately the mindscape of humanity to establish meaningful change that will let coming generations of sentient life succeed, but to do this we must enable our capacity to establish a bedrock of values that must never be forsaken when we investigate what is feasible in this unabashedly unsentimental quest to save the planet.Commanding hope comprises three strands. Honest hope means rigorously applying scientific methods and moral truths, and not thinking ourselves into a spiral of fantasy about what is possible. Astute hope recognizes the need to understand diverse peoples worldviews and aspirations. Powerful hope motivates us to work together, as agents with a compelling common purpose, to solve our problems.

Furthermore, we must diligently and deeply understand what is enough and combine it with what is feasible in our quest for a renewal of a world in peril. Feasible is no longer what the corporation, business-as-usual elite will chance, but rather it is tempered with imagination that fuses it to an enough that has solid principles of justice that include all of us; choosing what part of civilization is to be saved over another in a crisis is not an acceptable response, even in desperate times, Homer-Dixon warns us. We do not, however, give up on what has inherent value but is not immediately important, because we then lose the core of an authentic future. At the same time, honest hope prevents a turn towards unsubstantiated, unscientific decision making. Commanding hope creates the pathways we vitally need for this new world of equality and respect for Nature; it is gritty and resolved in its determination.

Sometimes an individual can instantly flip their worldview. At the age of 20, while hitchhiking abroad, I stopped to buy a drink of milk from a vendor. He poured the milk from an already opened carton. When I said I wanted it from a sealed carton, he furiously refused, saying how selfish and entitled North Americans were. I felt ashamed and realized he spoke the truth. That two-minute conversation changed my worldview with regard to wealth, food scarcity and inequality.Unfortunately, groups and nations modify their worldviews far more slowly than an individual can, and that change comes for the most part incrementally. Our worldviews connect us with our communities, stabilize our sense of who we are as individuals and groups through time, anchor our visions of a desirable and hopeful future…so were terrified when theyre threatened, explains Homer-Dixon. In response to potentially overwhelming crises, it is humanitys primary responsibility to push those static and seemingly intransigent destructive worldviews to the side and strive for migration to an entire world participating in renewing the future. Through learning about universal human temperaments, asking what Homer-Dixon calls binding questions, conducting thought experiments whereby we put ourselves in an opponents worldview, new cognitive-affective tools, and supporting our world values, humanity can forge positive worldviews that embrace a world-inclusive identity that makes perfect sense, as our greatest concerns are global in nature. Cultural identities are not sacrificed by doing so. Social order, fairness, opportunity and identity remain at the core of our worldviews and commitments.

Climate breakdown will challenge all of us and our worldviews, but how we respond to the possible chaos will determine our success in preventing the worse outcomes. Worldviews that help us surmount fear by inspiring rather than extinguishing the hope that motivates our agency have a great chance of flourishing.

Alternative worldviews and not rehashed older ones help us forge a better tomorrow. Worldviews that recognize human temperaments such as empathy, prudence and exuberance as well as commitments to opportunity, safety and justice and a shared global identity preserve not just a space for some form of democracy, but for all life too! Homer-Dixon speaks of an immortality project…that gives people and groups around the world broad possibilities to imagine, tell, and weave together their own hero storiesand to live them togetheras we move towards a shared vision of the future.Commanding hope becomes the emotional and rational energy and agency humanity must maintain to steadfastly leap through the inevitable dangers ahead of us. Homer-Dixon believes this jump is feasible and, he maintains, enough if we succeed in the transformation of our institutions, particularly our carbon-based energy system and our model of economic growth. This must be our aim in moving towards a sustainable and equitable future.

Please listen to the CBC Ideas interview with Thomas Homer-Dixon.

Hope: the enormous power to renew the world.

Lets speak about our individual worldviews by starting with a cartoon by Marc Roberts that shows a man putting his hand in a glass bottle. At the bottom of the bottle is a car. He reaches for it, and with his hand now enlarged with the car he cant get it out of the bottle. As he struggles helplessly a friend comes up to him and says, Youll have to LET GO of the car. Upon which, while still grasping the car, his face utterly distorted, he screams, NEVER!!! The cartoon appears in Thomas Homer-Dixons newly published book, Commanding Hope: The Power We Have to Renew a World in Peril. It depicts an obsessive mans outrage that he cant have everything he wants, and his worldview an important word in Homer-Dixons lexicon is one that has to change if people and the planet are to celebrate a return to ecological sanity by 2100.The possession of a car, for most people in the west who can afford it, is an undeniable right, even if the car brings all manner of ills to our world, including an acceleration of climate breakdown, the destruction of natural places, and questionable resource extractions that upend Global South vulnerable communities.All of this becomes personal, as I have just leased an electric car. Although I was determined never to get an internal combustion vehicle again, I couldnt help feeling uneasy when I viewed the cartoon. Was I the person depicted in the drawing? Was I hell-bent on obtaining a car regardless of the consequences for our planet? Lets face it: electric cars have their problems. Their manufacture and use cause pollution, and thats only the beginning of the dilemma. My rationale for driving an electric vehicle (EV) was interesting to contemplate and goes like this: poor bus transportation in my area; an ongoing pandemic, which means that taking a taxi can be risky, as previous passengers might have been infected; and the desire to take a vacation or get to a national park to cross-country ski or snowshoe this winter. All these clinched my resolve to get the car. Even though I know that not having a car is the best action, I felt I could contribute far less to climate breakdown with the use of the EV by not emitting fossil fuels, despite the fact that the production of the car does exactly that and were told it might take a couple of years before the car becomes carbon-free after all that energy to produce it is accounted for. Walking and continuing to use my bicycle around the area as my primary means of transportation are a good start, as well as not flying, I told myself. Nonetheless, I felt my hand reaching for that car, saying, Never!

We rarely dissect our private worldview or discuss what exactly the prevailing worldview is in the country where we live. Our worldview, born from our experiences, gives us a framework, gives us our personal identities, and links us to groups that include our families or to our place of birth. It incorporates our beliefs and values.

Homer-Dixon suggests that if we hope to have a better chance of pulling through the bottleneck of crises in this century, we need to have a shared global worldview thats generous, inclusive, trusting, and compassionate and that empowers us to live together more wisely on Earth. To hope to, as opposed to hope for, requires us to use our agency, our determination to create a better world. Wishful thinking wont get us there.

As well see in my next article, hope can be the motivational force that links us perpetually to an admittedly uncertain future, but we can always apply honest insights and honest hope about where we stand in order to truly ascertain if there is a reasonable chance to realize positive change. The possibility for a better world needs to start with truthful no-nonsense discourse. Although a detailed review of Commanding Hope will appear in my next article, I wish now to explore by an example my view on hope. It is my response to Homer-Dixons book.

A few years ago, when I was living in Britain, I tried (and am still trying) to put together a massive action that revitalizes at once the sense of climate urgency and, most importantly, the imagination necessary to change our destructive worldview of our place in Nature and of each other. Since Britain was the worlds driving force in the technological and societal changes that brought about the global Industrial Revolution and set in train the downward spiral into climate chaos, it can be argued that there is an ethical duty for Britain to be the leading inspiration to stop rapid climate change.

My vision is that by 2022 extensive partnerships will be in place for groups of people to set out from all corners of Britain on a walk to demonstrate their commitment to a zero-carbon economy/culture. Travelling in relays and converging from all directions, the groups will initiate a Great Circle of Britain to firmly establish an unshakeable resolve to transition rapidly away from the fossil-fuel economy/culture in Britain and embrace climate-/eco-friendly solutions. The Walk for Climate is a pilgrimage to the centre of Britain, both physically and spiritually. It seeks to find a way back to the strongest inclusive values we all can share. In order to do this we must include all people, not just those who already share our views. The Walk for Climate is a walk for solidarity with all of Nature. It brings all members of our communities together to seek out and actively put into place the potential that all communities possess. A renewed wisdom of the commons can include all of Nature and bring us to a place of peace and harmony. Through mindful consideration and a powerful sense of agency we can hope to change our own worldview. More to come.

Even after all this time the sun never says to the earth You owe me. Look what happens with a love like that. It lights the whole sky. – Daniel Ladinsky

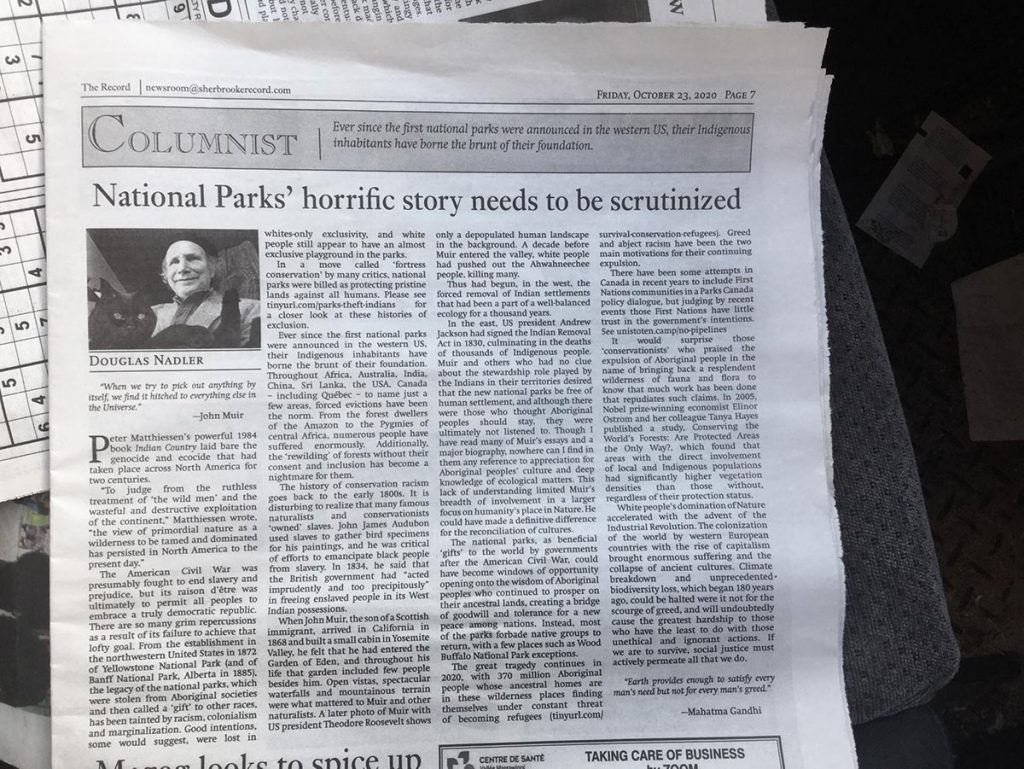

National Parks’ horrific story needs to be scrutinized

“When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.”

John Muir

Peter Matthiessen’s powerful 1984 book Indian Country laid bare the genocide and ecocide that had taken place across North America for two centuries. “To judge from the ruthless treatment of ‘the wild men’ and the wasteful and destructive exploitation of the continent,” he wrote, “the view of primordial nature as a wilderness to be tamed and dominated has persisted in North America to the present day.”

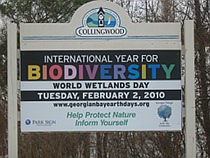

The American Civil War was presumably fought to end slavery and prejudice, but its raison d’être was ultimately to permit all peoples to embrace a truly democratic republic. There are so many grim repercussions as a result of its failure to achieve that lofty goal. From the establishment in the northwestern United States in 1872 of Yellowstone National Park (and of Banff National Park, Alberta in 1885), the legacy of the national parks, which were stolen from Aboriginal societies and then called a ‘gift’ to other races, has been tainted by racism, colonialism and marginalization. Good intentions, some would suggest, were lost in whites-only exclusivity, and white people still appear to have an almost exclusive playground in the parks.

In a move called ‘fortress conservation’ by many critics, national parks were billed as protecting pristine lands against all humans. Please see tinyurl.com/parks-theft-indians for a closer look at these histories of exclusion.

Ever since the first national parks were announced in the western US, their Indigenous inhabitants have borne the brunt of their foundation. Throughout Africa, Australia, India, China, Sri Lanka, the USA, Canada – including Québec – to name just a few areas, forced evictions have been the norm. From the forest dwellers of the Amazon to the Pygmies of central Africa, numerous people have suffered enormously. Additionally, the ‘rewilding’ of forests without their consent and inclusion has become a nightmare for them.

The history of conservation racism goes back to the early 1800s. It is disturbing to realize that many famous naturalists and conservationists ‘owned’ slaves. John James Audubon used slaves to gather bird specimens for his paintings, and he was critical of efforts to emancipate black people from slavery. In 1834, he said that the British government had “acted imprudently and too precipitously” in freeing enslaved people in its West Indian possessions.

When John Muir, the son of a Scottish immigrant, arrived in California in 1868 and built a small cabin in Yosemite Valley, he felt that he had entered the Garden of Eden, and throughout his life that garden included few people besides him. Open vistas, spectacular waterfalls and mountainous terrain were what mattered to Muir and other naturalists. A later photo of Muir with US president Theodore Roosevelt shows only a depopulated human landscape in the background. A decade before Muir entered the valley, white people had pushed out the Ahwahneechee people, killing many.

Thus had begun in the west the forced removal of Indian settlements that had been a part of a well-balanced ecology for a thousand years.

In the east, US president Andrew Jackson had signed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, culminating in the deaths of thousands of Indigenous people. Muir and others who had no clue about the stewardship role played by the Indians in their territories desired that the new national parks be free of human settlement, and although there were those who thought Aboriginal peoples should stay, they were ultimately not listened to. Though I have read many of Muir’s essays and a major biography, nowhere can I find in them any reference to appreciation for Aboriginal peoples’ culture and deep knowledge of ecological matters. This lack of understanding limited Muir’s breadth of involvement in a larger focus on humanity’s place in Nature. He could have made a definitive difference for the reconciliation of cultures.

The national parks, as beneficial ‘gifts’ to the world by governments after the American Civil War, could have become windows of opportunity opening onto the wisdom of Aboriginal peoples who continued to prosper on their ancestral lands, creating a bridge of goodwill and tolerance for a new peace among nations. Instead, most of the parks forbade native groups to return, with a few places such as Wood Buffalo National Park exceptions.

The great tragedy continues in 2020, with 370 million Aboriginal people whose ancestral homes are in these wilderness places finding themselves under constant threat of becoming refugees (tinyurl.com/survival-conservation-refugees). Greed and abject racism have been the two main motivations for their continuing expulsion.

There have been some attempts in Canada in recent years to include First Nations communities in a Parks Canada policy dialogue, but judging by recent events those First Nations have little trust in the government’s intentions. See unistoten.camp/no-pipelines

It would surprise those ‘conservationists’ who praised the expulsion of Aboriginal people in the name of bringing back a resplendent wilderness of fauna and flora to know that much work has been done that repudiates such claims. In 2005, Nobel prize-winning economist Elinor Ostrom and her colleague Tanya Hayes published a study, Conserving the World’s Forests: Are Protected Areas the Only Way?, which found that areas with the direct involvement of local and Indigenous populations had significantly higher vegetation densities than those without, regardless of their protection status.

White people’s domination of Nature accelerated with the advent of the Industrial Revolution. The colonization of the world by western European countries with the rise of capitalism brought enormous suffering and the collapse of ancient cultures. Climate breakdown and unprecedented biodiversity loss, which began 180 years ago, could be halted were it not for the scourge of greed, and will undoubtedly cause the greatest hardship to those who have the least to do with those unethical and ignorant actions. If we are to survive, social justice must actively permeate all that we do.

“Earth provides enough to satisfy every man’s need but not for every man’s greed.”

Mahatma Gandhi

Saving the planet begins with the food we eat

“Nature is declining globally at rates unprecedented in millions of years. The way we produce and consume food and energy, and the blatant disregard for the environment entrenched in our current economic model, has pushed the natural world to its limits.”

Living Planet Report 2020

We all know that the planet’s ecological balance is tottering. Multiple scientific reports on the health of Nature that show precipitous declines in both vertebrates and invertebrates seem to make no difference to how world governments, policymakers or individuals commit to urgent and beneficial actions for stopping the massive slide towards catastrophic extinctions. Please see wwf.ca/living-planet-report-canada-2020

While national government subsidies for fossil fuel companies and for conventional agriculture are far outstripping any grants and loans that support both renewable energies and organic farming, individual cities have made great efforts and are producing viable results in fighting climate change’s insidious ramifications for all life.

As individuals we can all do our bit to bring about a more harmonious planet through steadfast support for organic agriculture. More and more people are buying organically produced food, but conversations about why we should commit ourselves to an organic diet often end with a single individual’s health and don’t consider the vast benefits that can accrue for our planet’s wellbeing. This article looks at what we can each do every day for our farmers, ourselves and the Earth.

When we buy organic foods, we are not paying for synthetic pesticides and other chemicals, so the soil is not contaminated with a deadly cocktail of ingredients. Around the world our destruction of soil and its microorganisms is well documented. By not contributing to yet another assault on the planet’s ecology, we are saying that farmers’ lives are respected as well. When we refuse to buy these harmful concoctions, we are helping farmers to protect themselves and their families against many maladies.

Not long ago an organic farmer told me that an ornithologist had visited their farm and the documentation of birds living there was truly astonishing. Through not introducing synthetic fertilizers and herbicides to the land, this farmer has been contributing to a remarkable abundance of wildlife and plants. Insects that pollinate our food crops or are a prime food for birds and bats are able to find a refuge in ecologically robust soils. Water is cleaner too, so people living downstream are not subjected to an influx of toxic chemicals, which have frequently shown up near non-organic farms.

Local communities are beneficiaries of sound agrarian practices; in a real sense organic farming is an insurance plan for all beings. In his new book A Small Farm Future, farmer and social scientist Chris Smaje argues that organising society around small-scale farming offers the soundest, sanest and most reasonable response to climate change and other crises of civilisation—and will yield humanity’s best chance at survival.

There has been huge coverage of litigation cases of people affected by pesticides. I have seen first-hand the disastrous use of pesticides in the tropics. Pristine lands and people have been tragically impacted by pesticides that are manufactured in North America (even though they are banned here) and sold to poorer countries. This is outrageous. Furthermore, people in those countries who do not know how to read the instructions pertaining to those chemicals are putting themselves and their children at extreme risk. At least one instance is documented where a mother was storing pesticides in her kitchen! The World Health Organization estimates that up to 40,000 people die each year from pesticide poisoning.

Until people fully embrace the reality that Nature is us and we are Nature, organic farms will continue to be just a small percentage of North America’s agriculture. On top of this, the chasm between humans and the rest of Nature will not reduce as long as social injustices continue unabated. If our very lives are contingent on the wellbeing of the rest of Nature, surely inclusivity and respect must be first principles for all our interactions. Social justice must flourish first.

Genetically modified organisms are forbidden in organic farming practices precisely because there are too many unknowns regarding their impacts on Nature. Because some humans believe that genetic manipulation has brought some successes in growing food, however, the capitalist drive towards unleashing a full-scale assault on Nature has been thought to be inevitable. It is not.

Organic farms are generally not monocultures. Diversity is a key ingredient in all ecological settings. Saving heritage seeds is an important and integral contribution to protecting communities’ resilience and independence, and there is cultural significance in growing seeds that have long been part of a community’s heritage. Organic farming celebrates what is local as well as our heritage. What is locally supported also creates strong social justice practices and encourages a love of place. Organically produced seeds are a great way to build community and are something we can seek out for our own gardens.

Please also consider buying food from local farmers. It is easy to do. Baskets of food can be picked up every few weeks at certain farms. Community Supported Agriculture enables family farms to prosper. Family Farmers Network brings together more than 130 organic farms in Québec and New Brunswick and can help you locate a farmer who can supply you with a regular basket of organically produced food. Here are two such farmers in our local area:

La Boîte à Légumes

Racines & Chlorophylle

Another way to have healthy, nutritious organic food is to buy your nuts, flour, beans and many other items online through NousRire, an organic buying group that delivers to pick-up points throughout Québec: nousrire.com

There are several organic food shops in town that can supply your day-to-day needs, as well as regular farmers’ markets such as Marché agricole de Lennoxville and Marché de la gare, Sherbrooke.

This is apple season, and it’s an opportunity to visit La Généreuse, which featured in an earlier article in The Record and is just 15 minutes away from Lennoxville. The farm produces several varieties of organically grown apples as well as delicious home-pressed apple juice. lagenereuse.com

There are many ways to help the planet, and our food choices are a major part of this. Even a small change can make a difference.

A tale of two dinner parties

“Given the right conditions, any society can turn against democracy. Indeed, if history is anything to go by, all societies eventually will.”

– Anne Applebaum

“You want it darker.” – Leonard Cohen

Anne Applebaum’s new book Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism tells of her experiences with powerful right-of-centre political figures and makes the case that our democracies are in mortal jeopardy of being utterly eroded. She takes us on a tour to many European countries that are in the throes of becoming one-party states.

The book is not meant to be a scholarly treatise on the growing rise of authoritarianism, although undoubtedly Applebaum is capable of writing one, having won a Pulitzer Prize as a historian for her writing on the Russian gulag. Twilight of Democracy focuses on the people she feels are destroying democracy. Most of those she writes about were once her friends and one was even a future head of state, but they are no longer speaking to her. (It’s important to understand that she herself is a conservative.) In some instances they are the intellectuals and power brokers who allow one-party regimes such as those now found in Hungary, Poland, China, the Philippines, Venezuela and Russia to flourish. She calls these disgruntled people “clerics”: the enablers of would-be despots. Most of them, she feels, have not felt appreciated in democratic societies and desire more power. Donald Trump’s and Boris Johnson’s angry right-wing “what’s in it for me?” acolytes are helping to dismantle democratic states. Truth is the last thing these “advisers” wish to discuss, and “alternative facts” are the way to create division.

Applebaum speaks of “restorative nostalgia,” which is used to rekindle a nation’s supposed past “greatness.” The narrative goes like this: the nation has become a shadow of its former self; the nation’s identity has been taken away and replaced with something less heroic. She warns, of its proponents, “All of them seek to redefine their nations, to rewrite social contracts, and, sometimes, to alter the rules of democracy so that they never lose power. Alexander Hamilton warned against them, Cicero fought against them. Some of them used to be my friends.” She adds, “Eventually, those who seek power on the back of restorative nostalgia will begin to cultivate these conspiracy theories, or alternative histories, or alternative fibs, whether or not they have any basis in fact.” Sound familiar?

For many people in the UK who support Brexit it is the EU that has sapped the true greatness of Britain. For Trump’s restorative nostalgia gimmick “Make America Great Again” to work, it must have a list of ills that have befallen the USA for which Trump points the finger of blame at Democrats, immigrants, protestors/agitators, Black Lives Matter supporters, gun-control advocates, scientists, anti-fascists, climate change activists and even the coronavirus lockdowns that necessitate masks and social distancing.

Understand that “reflective nostalgia” is quite different. We might study the past or mourn the past, but we realize that in fact life was more difficult then. Those old photographs, though they might have us romancing bygone days, are not going to help us revive those times again.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s book The Gulag Archipelago, which was published in 1973, gives us a nightmarish glimpse into the vast Russian prison holding areas. It tells us as much about the insane Kafka-like bureaucracy and Russian dictatorships as about the prisoners caught up in horrific, surreal incarceration. Only raw violent power is recognized as being worth pursuing. Solzhenitsyn’s book should be a reminder of how low all societies could descend.

It’s as if we need to find enemies so that we can justify our own insecurities and create a tribal response based on the fear of the “other.” This is not 1930s politics, but political camps have now metamorphosed into a redrafted belligerency. Words such as “freedom” have become the calling cards of white supremacists, though with that word they would take away the freedom of others.

America has hundreds of militias. The US constitution always has allowed for that, but since Trump came to Washington those militias have come off the firing range and into cities such as Portland, Oregon.

“The public embrace of militias and paramilitaries is clearly recognizable authoritarian behaviour,” says Steven Levitsky, co-author with Daniel Ziblatt of How Democracies Die. Veteran journalist Dahr Jamail concurs. In an interview with Truthout’s Patrick Farnsworth, he ponders, “Are we going to see clearly that we live in an autocratic state? … It also means that we are entering in an extremely darkening age, where whatever stress and chaos and loss that we see today, this is really just a prelude of what’s coming.”

Hannah Arendt wrote persuasively in the second half of the 20th century about fascism: “Totalitarianism in power invariably replaces all first-rate talents, regardless of their sympathies, with those crackpots and fools whose lack of intelligence and creativity is still the best guarantee of their loyalty.” [Origins of Totalitarianism]

A levelling of capabilities and talents goes with the kinds of regime that embrace a blind loyalty to their leader. Authoritarianism rewards loyalty and creates corruption and mediocrity in government, as opposed to meritocracy, whereby talented people are chosen and moved ahead on the basis of their achievements.

Last Saturday’s Guardian carried an article by Nick Cohn titled “The meritocracy has had its day”: “Public service jobs once went to people who knew what they were doing. Boris Johnson would rather promote a courtier.” Take for example Australia’s ex-prime minister Tony Abbott, who has recently been appointed as an adviser to the UK government’s board of trade and is a climate denier.

Although many government administrations reward their donors and party faithful, present-day right-wing regimes, including the Trump administration, have severely harmed democracy by promoting utterly unsuitable and undeserving individuals to positions within the highest levels of government. In fact, the march towards totalitarian regimes requires that arm’s-length government-oversight commissioners, who can monitor compliance to high ethical standards in governance, be kicked out. After all, Benjamin Disraeli said, “What is a crime among the multitude is only a vice among the few.”

Twilight of Democracy starts with a dinner party in 1999 and ends with one in 2019, both at Applebaum’s home. Although there were some return guests, some people she knew in 1999 were no longer friends and had become clerics of one-party states. This microcosm of the polarization of society now taking over the world and shredding democracy is one that she feels strongly must be confronted. The risks for our world are far too great. “Participation, argument, effort, struggle” are needed, as well as “some willingness to push back at the people who create cacophony and chaos.”

It is up to us to be vigilant, to speak out against the undermining of our hard-won democracy, and to use the power of our votes.

“Ring the bells that can still ring.” – Leonard Cohen

Interview with Nick Gottlieb: giving young people a public voice

Nick Gottlieb is the author of Sacred Headwaters, a bi-weekly newsletter that gives critically important insights into how we can protect our planet.

Nick, you write that Sacred Headwaters “aims to guide a co-learning process about the existential issues and planetary limitations facing humanity and about how we can reorient civilization in a way that will enable us to thrive for centuries to come.” What have been the catalysts driving you towards a co-learning and inclusive approach in these newsletters?

Climate change is a symptom of much deeper problems in the social, political and cultural structures that we collectively call human civilization. Overcoming those problems requires reimagining what we value as humans and what we expect from life. But the systems we’re trying to replace are so embedded that they constrain the way we think and the scope of what we perceive as possible. I chose this format for my newsletter because I – perhaps naively – believe that if people learn enough about how the system is failing and why, they’ll come to recognize the patterns of that system in their own cognitive frameworks, their own minds, and through that recognition free themselves to begin the process of change.

You move from climate change and planetary boundaries to current politics and ideas. “Defunding the Police,” “Indigenous Ways of Knowing,” “Environmental Racism” and “Degrowth” are a few of the titles of the newsletters. What are your overarching goals in sharing these newsletters?

The climate movement tends to focus on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, but this narrative fails because it identifies them as the “root cause.” We’ve known that GHG emissions cause global warming that threatens our way of life since at least 1959. In 1992, 88% of Americans believed global warming was a serious problem. But we live in a world where companies are incentivized to externalize costs and maximize “profit,” leading them to actually fight against solving climate change despite knowing full well its implications. We’ve seen parallel stories play out over and over again; climate change is just one manifestation. I’ve been writing about issues like environmental racism to try to draw those connections for readers, to make clear that if we want to survive the climate crisis, we need to recognize that it is a symptom of a much more invasive disease than GHG emissions.

In your newsletter “Introduction to Systems Thinking,” a memorable sentence, “The earth is a system,” stands out. You describe Sacred Headwaters as being “about the systemic nature of everything.” Can you explain this, please?

We have a tendency towards reductionism rooted in what our culture thinks of as “science”: we isolate every problem so we can solve it, but the real world is governed by deep complexity and interconnectedness. This is true in ecological systems, as we can see in the speed with which we’re exceeding most of the modelling of global warming’s impacts, and also in the systems of organization that govern human society. Climate change, environmental racism and widespread inequality are interrelated problems with systemic causes. My goal is to elucidate the deeper causes of these crises to enable more people to envision a world without them.

How do you feel about your generation’s response to the Earth’s crises? What, if anything, do think it needs to do better?

Personally, I don’t like the generational narrative. This isn’t any one generation’s problem. We need to rebuild our lost cultural capacity for multi-generational thinking and planning. That said, I think the millennial generation is facing some unique challenges that position us well to be a generation of change. We are the first generation in the modern era that’s worse off than our parents’. We can’t afford houses, wages are stagnant, jobs are rare. The life our parents had is not an option for most of us, but as challenging as that is it’s also a gift, because it’s forcing us to reimagine what life looks like, allowing us leeway to experiment, to divine what a life that’s compatible with a liveable future might look like. The more of us who give up the false hope that we can have the lives our parents enjoyed, the better.

What direct actions do you feel we must commit ourselves to in order to save our planet’s ecological integrity?

The oil industry is dying. Even before the pandemic, big players in finance were getting out of the fossil fuel industry. It’s only a matter of time, but those in power are trying to hang on. Here in Canada the government is doubling down on new oil and gas infrastructure that will likely never be profitable. This transition period – the next few years, probably – is important because once infrastructure is built it’s hard to stop using it. In a few years no one will be trying to build LNG export facilities or drilling for new oil and gas, but in the interim we need to do what we can to ensure that new infrastructure doesn’t get built. Part of that is what movements like Extinction Rebellion are doing, and it’s humbling to see people like Dr. Takaro hanging from trees in Burnaby to stop the Trans Mountain expansion.

What do you wish to flourish as a result of your efforts?

The big picture answer is that I’m working to radicalize as many people as I can. We will see untold human suffering in the coming decades and likely the end of what we call civilization if we don’t make radical changes in every aspect of our society. The more people who realize this, the better our chance to effect change. On a small scale, one friend credited me with motivating her to install solar on her house and buy an electric vehicle; another told me she moved to a small town to try to minimize the impact of her lifestyle, in part because of my work. These don’t sound like much, but they add up, and they mean a lot to me personally.

Bewildered! Where do we go from here?

“Law and order exist for the purpose of establishing justice and…when they fail in this purpose they become the dangerously structured dams that block the flow of social progress.”

– Martin Luther King, Jr.

The best of all possible worlds can only come about if the most compassionate elements of humanity prevail. The world, encircled with a supercharged capitalism and would-be tyrants, must choose a path towards either love or destruction. Sadly, it has taken the coronavirus to shake up the world’s iniquitous economies, and the racist death of a man to push us to the brink. To where, though?

This whole article was supposed to be about trying to make sense of Michael Moore’s Planet of the Humans, which was released on YouTube on Earth Day (April 22), but more pressing concerns needed airing. It is because it represents a pattern of injustices that I discuss it at all. I recommend that you watch this contentious documentary and its many unfounded assertions regarding renewable energy and green activists, if only because it mentions, though all too briefly, pertinent and important issues (population and overconsumption) that have relevance for our precarious lives. Though I’d agree with the makers that green technological fixes won’t solve the world’s problems, the film is a shoddy mixture of ill-founded allegations, and, for many, Michael Moore’s ‘green’ reputation is in tatters. Most egregiously, we are told that the green movement is built on fossil-fuel money and that Bill McKibben, one of its best-known activists, is a fraud. The film is a compendium of half-truths that pits us against each other, while climate deniers buy more oil stock. What a way to celebrate Earth Day! Moore does us a great disservice, as we need truth more than ever now, not a disingenuous film.

On Sunday, June 7, Sherbrooke protested the killing of George Floyd by a police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota two weeks ago. An estimated 2,000 people, mostly under the age of 40, met in front of the police station to listen to speeches addressing this grotesque murder and institutionalized racism. For nearly nine minutes they (but not the police who were watching) knelt in silence with fists outstretched to bear witness to the many black and indigenous people discriminated against. Police violence and racism are a cancerous growth. At the same time, billionaires’ greed and influence in government are accelerating the alienation and suffering of those in poverty, while there is an unprecedented push by those in power to dismantle any semblance of democracy. The “rule of law,” enforced by readily compliant police for many centuries, has propped up the aristocracy and now the corporate agenda. Remember that Germany’s laws allowed Hitler to ravage Europe. Authoritarian regimes such as China and Russia are police states. Under Trump, the US is, as Noam Chomsky terms it, a failed state. Israel appears to be no better.

People around the world have condemned the racism found in their countries. Western racism has a long history. In Bristol, UK, also on June 7, the statue of an extremely wealthy 17th-century slave trader, Edward Colston, was toppled and thrown into the harbour. Colston made a fortune enslaving 80,000 Africans and transporting them to America and was heralded as “one of the most virtuous and wise sons” of Bristol as a result of his philanthropic zeal for that city. How could it be that for 300 years people chose to disregard the indisputable fact that this philanthropy was founded on dirty money?

In a message for World Environment Day on June 5, Vandana Shiva urged, “We need to shift from the assumption that violating planetary boundaries, ecosystem boundaries, species boundaries, and human rights is a measure of progress and superiority—to creating economies based on respecting ecological laws and ecological limits, and respecting the rights of the last person, the last child.”

There is no doubt that this decade will bring all sentient beings to a crossroads created by humans. Have the months of reflection and quietude imposed upon the human world by Covid-19 given us the courage to reach out towards inclusivity and give up a collective madness that until now has created more and more suffering for the planet, or will “business as usual” return with a vengeance and smash our beautiful world?