Climate justice and ethics: some thoughts

“We must use this moment as crucial leverage to push the planet in a new direction. Let us try. If we succeed, then we have risen to the greatest crisis humans have ever faced and shown that the big brain was a useful evolutionary adaptation. If we fail—well, we better to go down trying.”

Climate activist Bill McKibben

After experiencing a record-breaking heatwave of 45.9C in France last week, scientists have concluded that the heatwave was at least five times more likely because of climate change.

The climate crisis is real, so here’s a question: in order to achieve climate justice, since most people seem reluctant to change their damaging habits, what if individually and nationally we put into law strict carbon budgets? For example, if you flew frequently, your budget to indulge would be used up more quickly. Once you had depleted your budget, if you wished to continue to travel by air, either a massive tax of, say, 1,000% would be levied on each ticket, or you’d simply be prohibited from flying.

Nationally, one more pipeline carrying dirty oil would exceed Canada’s carbon budget. The world’s population will be close to 10 billion by 2050 – World Population Day is on July 11 – and the individual carbon budget would need to shrink accordingly.

In the short term, before there is a mandatory budget for climate justice, should we begin to speak about the criminal liability of governments and individuals for excessive use of fossil fuels? If this sounds too radical, consider that this conversation has already started in the USA with a group of young people suing the federal government for just that reason.

We each need to question our own engagement in activities that will accelerate the breakdown of our climate, irrecoverable loss of biodiversity, and the impoverishment of billions of people. The term ‘climate apartheid’ is being used to describe how the wealthiest 10% of the population is ruining the lives of the other 90%. The urgency with which this conversation needs to take place becomes clear with a NASA report published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences last month that a massive shrinking of sea ice is occurring in Antarctica, raising sea levels.

It’s as if we delegate our ethical responsibilities to our representatives in government to fix the problems of this world after voting them into power, thereby absolving the individual of doing anything. Back in 1992, 1,670 world-renowned scientists signed the World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity, which concluded with these words: “A new ethic is required – a new attitude toward discharging our responsibility for caring for ourselves and the earth. We must recognize the earth’s limited capacity to provide for us. We must recognize its fragility. We must no longer allow it to be ravaged. This ethic must motivate a great movement, convincing reluctant leaders and reluctant governments and reluctant peoples themselves to effect the needed changes.”

In 2018 over 15,000 scientists endorsed a second Warning to Humanity. Clearly, government bodies, elected by their citizens, have failed to promote a new Earth ethic that perpetuates a healthy, inclusive world. But make no mistake: individuals have failed too.

In 1953 the American naturalist and writer Aldo Leopold had this to say: “One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds… [An ecologist] must be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise.” Ten years later, the corporate vehemence and denial that attended the release of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring essentially summed up what most biodiversity scientists, climate justice activists and human rights advocates experience even today. So to say that the science is under siege is an understatement. Trump and Harper remain the kingpins for such activities, but Trudeau’s double-speak on supporting oil pipelines that he says will give us the money to wean ourselves away from fossil fuels speaks volumes. Many believe this to be a criminal activity. EcoJustice, Canada’s legal advocates for Nature, said: “The reality is that the government can put Canada on the path to a safe climate future… or it can push this pipeline through. It cannot do both.”

A new vibrant Earth dialogue has started. Will you join it?

Celebrating World Biodiversity Day with Action

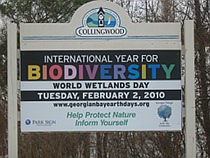

The United Nations International Day for Biological Diversity (May 22) focuses on biodiversity as the key provider for our food and health. Also called World Biodiversity Day, it emphasizes the critical link between a healthy ecology of diverse communities of beings and the viability of long-term human welfare.

It has long been known that the climate emergency has become a key catalyst in negatively transforming our planet’s ability to provide food and sustenance for humans and all other animals. Whereas past mass extinctions of species occurred over millions of years, the current mass extinction of flora and fauna started with the Industrial Revolution and most disturbingly has accelerated to new destructive heights in the last 25 years. Not only have rising carbon dioxide levels and ocean temperatures caused vast changes to marine life (notably through the destruction of many coral reefs), but also the stability of our atmospheric climate has been weakened to such an extent that the vast majority of recorded heatwaves have occurred in the last 25 years, resulting in ravaged places with seemingly unending wildfires and, paradoxically, flooding. California is a case in point. All of these crises have been spawned by western countries’ apparent total disregard for other people as well as for their planetary cousins.

In his recently published book Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out? climate activist Bill McKibben outlines the greed, the misinformation and ultimately the culpability of corporations such as Exxon that knew back in the 1970s that fossil fuels contributed to climate instability. He also details the deceit of coal baron billionaires who foster a new age of ecological disasters. Multinationals with untold millions at their disposal have lobbied governments to push for an agenda of the super-rich that celebrates hyper-individualism at the expense of social justice and a chance of prosperity for many of the world’s poorest people. Governments, including ours, have succumbed to these groups and individuals to such an extent that an insidious plutocracy has put democracy in dire peril and threatens to strip the Earth of its insects and amphibians as well as most other wildlife. People who dare to confront the anti-Earth lobbyists are suffering dire consequences.

May 20 is World Bee Day, acknowledging the crucial part pollinators play in providing food for all beings. Yet the Canadian government, unlike France and other European countries, refuses to ban neonicotinoid pesticides, which have been shown to be toxic to bees and other insects.

Recently, Louis Robert, a Québec government scientist, gave the CBC documentation showing that the pesticide industry controlled some of the decision-making abilities of the Québec Ministry of Agriculture. As a result, he lost his job. Please see tinyurl.com/whistleblower-pesticides-fired

The climate emergency and the acceleration of the biodiversity crisis have caused a monumental shrinking of habitat. The abandonment of lands due to sea level rise and extended heatwaves has pushed flora and fauna populations to the brink of extinction, and humans are not exempt from this carnage. Consider the 93 deaths in Québec last summer from the extreme heat. Most of those people were elderly and/or living in poverty.

Climate change and biodiversity loss have already shrunk our cultural, economic and physical connections to this planet. Increasingly, humans and other sentient beings are becoming climate migrants driven from forest or farming communities by drought, floods or the destruction of their native soils. Contaminated river and coastal villages and polluted cities are making life unbearable.

McKibben’s Falter speaks of non-violent resistance and engagement in the face of entrenched power. But let’s first call this tragedy by appropriate names. The 16-year-old climate activist Greta Thunberg put it this way: “It’s 2019. Can we all now call it what it is: climate breakdown, climate crisis, climate emergency, ecological breakdown, ecological crisis and ecological emergency?”

It is time to firmly resist fossil fuel lobbyists. At the same time governments must stop giving obscene subsidies to those same Earth destroyers and support solar power.

In marking World Biodiversity Day we need to affirm the right to move away from ecocide and once more embrace this planet’s fantastic diversity. Only then can we chart a course towards a new, just balance that respects and nurtures all life on Earth.

To celebrate all wildlife, please watch this amazing video featuring the monarch butterfly: www.thisiscolossal.com/2019/05/monarch-butterfly-sounds

Nature and Community Activism

The May 6 headline said it all: Human Society Under Urgent Threat from Loss of Earth’s Natural Life

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/may/06/human-society-under-urgent-threat-loss-earth-natural-life-un-report

Our Earthly inhabitants are at a dangerous crossroads. In 2002, the biologist E.O. Wilson said that humans and the other species on Earth are caught in the bottleneck of an accelerating ecological crisis. Industrial countries have lost their way, without the certain knowledge that we are capable of extracting ourselves or indeed willing to exit this relentless multi-faceted extinction squeeze on species ranging from insects to primates. Within just 150 years they have succeeded in threatening our planet’s viability. If humans won’t acknowledge and actively respond to the dangerous situation we have drifted into, we will sink with the remaining creatures into the quagmire of our making, for without pollinators, soil and seas we are doomed.

The daily scientific news is relentless: unless we change our ways, and soon, climate change will cast an unchangeable veil of greyness across the planet. The U.N. Climate Report last November warned that we have 12 years to drastically reduce our fossil fuel emissions so that global temperatures don’t exceed 1.5 °C. As the respected environmental activist Bill McKibben has stated through his many books, starting with his 1989 treatise The End of Nature, the world is rapidly moving towards “climate chaos”.

On May 6 this year The U.N. Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services published its critically important 1,800-page Global Assessment Report. The outlook for us and our fellow Earthlings is becoming progressively bleaker. This fact is well established, but North Americans, and their politicians in particular, behave as if there were no planetary bio-climatic crisis. Québec’s Biodiversity Atlas demonstrates how serious the situation is in southern Québec, but few people know of this document.

Yet one single person can inspire the rest of us to rise to the enormous challenge, “where the voice that is in us makes a true response, where the voice that is great within us rises up”. Last year a schoolgirl named Greta Thunberg did just that, galvanizing her fellow teenagers to find their voices and demand that adults protect them from the ravages of climate change.

After centuries of feeling alienated from Nature, can we find our way back home – our only home? The path is tortuous, but we can focus on a vision that will allow us to succeed. Earthly community is the way forward. The 17th-century English poet John Donne wrote: “No man is an island entire of itself. Every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main… Any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind…” Now we know that our involvement must move to embrace all creatures.

People are finally reacting strongly to government indifference, and speak of the climate and biodiversity crisis as a deeper symptom of our general malaise: increasing social injustice, over-population and capitalism’s mantra for unlimited growth on a finite planet are among the grave concerns that are being voiced. A multitude of global initiatives have gained traction, including the Green New Deal championed by the youth-led Sunrise Movement. The recent 10-day Extinction Rebellion civil disobedience actions across the world shook up British politicians to declare a climate emergency. The student climate strikes here in Canada and globally have been hugely successful in creating a momentum that promises legislative change.

One example of how school and community can become involved in protecting and respecting Nature is Cookshire Elementary School’s transformation last year into a Living School, incorporating Nature into all aspects of learning so that the students and staff can benefit mentally and physically from a connection with the natural world. Dawson College in Montreal is a partner in the initiative, and St. Francis Valley Naturalists’ Club is sponsoring guest lecturers. Representatives from universities have visited the school, which it is hoped will serve as a model for other schools and campuses to follow.

My purpose in writing these articles is to celebrate what is best locally and globally that can bring us together to confront the ‘great thinning’ of our fellow inhabitants on this planet and create a viable community that includes all of us, not just humans. May 22 is International Day for Biological Diversity. Let’s come together to celebrate our interdependence with the rest of Nature.

Thinking about emissions

Global emissions rose in 2018 with the USA increasing its emissions after three years of decline. Understanding the contributing factors is not enough — action at all scales is needed.

Rescuing Paris

To achieve the Paris climate goals, the private sector and sub-national governments need to fill the void left by unambitious national government efforts.

The climate and the oceans are in crisis

Dr. Peter Carter and others are warning the planet and all of humanity is in peril due to the consequences of the industrial age. Host Jack Etkin blames the media for not informing the public just how grave the danger has become. This is the complete interview. Edited versions were shown on ShawTV Victoria and Vancouver.

Global Warming of 1.5º C

The Special Report was developed under the joint scientific leadership of Working Groups I, II and III with support from WGI TSU. The IPCC is currently in its Sixth Assessment cycle. During this cycle, the Panel will produce three Special Reports, a Methodology Report on national greenhouse gas inventories and the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6).

Sutton’s rich tapestry of living brings back a traveller to stay.

When I returned to Sutton last summer I had been away for more than 50 years. Although I remembered cycling up plenty of hills and sitting by rivers, it was the mountain walks I took in July that brought back to me the Appalachian character of the place: its abundance of tree species, the familiarity of rock formations, how trees will shape themselves around these boulders, the lakes… But even more so, the aroma of the soil welcomed me back after an absence that had taken me to many different landscapes. Finally, like Lemuel Gulliver, I felt I had arrived home after a long and sometimes turbulent world voyage. And I certainly know what makes me feel comfortable in a town: access to woods, an engaged cultural community, a vibrant outdoor market, people who will stand up to protect Nature and our mental and physical health, a variety of sports for all seasons, Tai Chi, yoga and dance, as well as others to play music with. I would be remiss if I left out my strong desire to be completely fluent in French. All of this Sutton can offer its community, plus enduring friendships.

Sutton’s character is defined by the beauty of its natural terrain, but that can change. I have witnessed this, unfortunately, elsewhere in the world. Yet in Ontario I have worked with teenagers who realised that the mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions was an urgent necessity if their planet was to be a key source of inspiration for human creativity and the enduring protection of life on Earth as we know it. Human spiritual growth can push back the threat of ecocide. Scientific facts alone will not engage most people on the topic of climate change. Young people get excited by being in wilderness, starting a community garden or spending time on an organic farm. I have witnessed their commitment to zero-emission projects such as putting up clothes lines across a community, or hand-mowing grass for residents rather than using powered machines, thereby protecting Nature and their health.

Just as importantly, young and older people alike need to bring poetry’s primeval energy back to the description of Nature. Robert Macfarlane’s book Landmarks and The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd celebrate Nature through poetic, localised vocabulary. Perhaps that most banal and disrespectful of words ‘environment’ will disappear if we can embrace a profound respect for other creatures. No aboriginal group on the planet would use such a condescending word to describe all of Nature. As a Western society we are deeply disconnected from the natural world, and the crisis of climate change will never be overcome by technology alone. The technocratic and clinical word ‘environment’ is just one more symptom of the West’s inability to respect and relate to other species, unless we speak of cats, dogs and horses – who are, for the most part, enslaved by humans.

I have lived near ski and tourist towns before and there are certainly challenges that arise. Sutton is no different. Houses built for ski visitors overlook and encroach on our wonderful trails. The massive pollution produced by transportation of goods and construction materials across the border as well as by motorcycles and cars has made Rue Principale, with its narrow passageway so close to the shops, a health concern, particularly for elderly and very young people. The prestigious medical journal The Lancet recently commissioned a report on air pollution that lays out the dangers for people aged over 60 and pregnant women from walking on polluted thoroughfares. I might add that small children walking or being transported in buggies along Rue Principale, as well as outdoor staff and clientele at the restaurants, are all at risk from diesel truck emissions in particular.

There is hope. Electric vehicles are here. Companies such as UPS are transforming their fleets. Sutton needs to work with Québec and the federal government towards implementing mandatory pollution-free zones in our towns. Sutton is happily a bicycle haven. Let’s encourage such activities. Sutton’s new mayor, Michel Lafrance, assured me that the town’s new municipal council is committed to being “green”. We need to focus on ‘road ecology’, to mitigate the impacts roads have, not only in wild places but also in urban settings. Fortunately, the not-for-profit Québec-based Corridor appalachien is keen to educate and help us lessen the destructive effects of roads.

2018 can be the year to bring to fruition many community goals. Let’s make it happen.

A Biologist’s Manifesto for Preserving Life on Earth

By E.O. Wilson

1

We are playing a global endgame. Humanity’s grasp on the planet is not strong; it is growing weaker. Freshwater is growing short; the atmosphere and the seas are increasingly polluted as a result of what has transpired on the land. The climate is changing in ways unfavorable to life, except for microbes, jellyfish, and fungi. For many species, these changes are already fatal.

We are playing a global endgame. Humanity’s grasp on the planet is not strong; it is growing weaker. Freshwater is growing short; the atmosphere and the seas are increasingly polluted as a result of what has transpired on the land. The climate is changing in ways unfavorable to life, except for microbes, jellyfish, and fungi. For many species, these changes are already fatal.

Because the problems created by humanity are global and progressive, because the prospect of a point of no return is fast approaching, the problems can’t be solved piecemeal. There is just so much water left for fracking, so much rainforest cover available for soybeans and oil palms, so much room left in the atmosphere to store excess carbon. The impact on the rest of the biosphere is everywhere negative, the environment becoming unstable and less pleasant, our long-term future less certain.

Only by committing half of the planet’s surface to nature can we hope to save the immensity of life-forms that compose it. Unless humanity learns a great deal more about global biodiversity and moves quickly to protect it, we will soon lose most of the species composing life on Earth. The Half-Earth proposal offers a first, emergency solution commensurate with the magnitude of the problem: By setting aside half the planet in reserve, we can save the living part of the environment and achieve the stabilization required for our own survival.

Why one-half? Why not one-quarter or one-third? Because large plots, whether they already stand or can be created from corridors connecting smaller plots, harbor many more ecosystems and the species composing them at a sustainable level. As reserves grow in size, the diversity of life surviving within them also grows. As reserves are reduced in area, the diversity within them declines to a mathematically predictable degree swiftly—often immediately and, for a large fraction, forever.

A biogeographic scan of Earth’s principal habitats shows that a full representation of its ecosystems and the vast majority of its species can be saved within half the planet’s surface. At one-half and above, life on Earth enters the safe zone. Within that half, more than 80 percent of the species would be stabilized.

There is a second, psychological argument for protecting half of Earth. Half-Earth is a goal—and people understand and appreciate goals. They need a victory, not just news that progress is being made. It is human nature to yearn for finality, something achieved by which their anxieties and fears are put to rest. We stay afraid if the enemy is still at the gate, if bankruptcy is still possible, if more cancer tests may yet prove positive. It is our nature to choose large goals that, while difficult, are potentially game changing and universal in benefit. To strive against odds on behalf of all of life would be humanity at its most noble.

2

Extinction events are not especially rare in geological time. They have occurred in randomly varying magnitude throughout the history of life. Those that are truly apocalyptic, however, have occurred at only about 100-million-year intervals. There have been five such peaks of destruction of which we have record, the latest being Chicxulub, the mega-asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs. Earth required roughly 10 million years to recover from each mass extinction. The peak of destruction that humanity has initiated is often called the Sixth Extinction.

Many authors have suggested that Earth is already different enough to recognize the end of the Holocene and the beginning of a new geological epoch. The favored name, coined by the biologist Eugene F. Stoermer in the early 1980s and popularized by the atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen in 2000, is the Anthropocene, the Epoch of Man.

The logic for distinguishing the Anthropocene is sound. It can be clarified by the following thought experiment. Suppose that in the far-distant future geologists were to dig through Earth’s crusted deposits to the strata spanning the past thousand years of our time. They would encounter sharply defined layers of chemically altered soil. They would recognize signatures of rapid climate changes. They would uncover abundant fossil remains of domesticated plants and animals that had replaced most of Earth’s prehuman fauna and flora. They would excavate fragments of machines, and a veritable museum of deadly weapons.

3

Biodiversity as a whole forms a shield protecting each of the species that together compose it, ourselves included. What will happen if, in addition to the species already extinguished by human activity, say, 10 percent of those remaining are taken away? Or 50 percent? Or 90 percent? As more species vanish or drop to near extinction, the rate of extinction of the survivors accelerates. In some cases the effect is felt almost immediately. When a century ago the American chestnut, once a dominant tree over much of eastern North America, was reduced to near extinction by an Asian fungal blight, seven moth species whose caterpillars depended on its vegetation vanished. As extinction mounts, biodiversity reaches a tipping point at which the ecosystem collapses. Scientists have only begun to study under what conditions this catastrophe is most likely to occur.

Human beings are not exempt from the iron law of species interdependency. We were not inserted as ready-made invasives into an Edenic world. Nor were we intended by providence to rule that world. The biosphere does not belong to us; we belong to it. The organisms that surround us in such beautiful profusion are the product of 3.8 billion years of evolution by natural selection. We are one of its present-day products, having arrived as a fortunate species of old-world primate. And it happened only a geological eye-blink ago. Our physiology and our minds are adapted for life in the biosphere, which we have only begun to understand. We are now able to protect the rest of life, but instead we remain recklessly prone to destroy and replace a large part of it.

4

Earth remains a little-known planet. Scientists and the public are reasonably familiar with the vertebrates (fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals), mostly because of their large size and immediate visible impact on human life. The best known of the vertebrates are the mammals, with about 5,500 species known and, according to experts, a few dozen remaining to be discovered. Birds have 10,000 recognized species, with an average of two or three new species turning up each year. Reptiles are reasonably well known, with slightly more than 9,000 species recognized and 1,000 estimated to await discovery. Fishes have 34,000 known species and as many as 10,000 awaiting discovery. Amphibians (frogs, salamanders, wormlike caecilians), among the most vulnerable to destruction, are less well known than the other land vertebrates: a bit over 6,600 species discovered out of a surprising 16,000 believed to exist. Flowering plants come in with about 270,000 species known and as many as 94,000 awaiting discovery.

Earth remains a little-known planet. Scientists and the public are reasonably familiar with the vertebrates (fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals), mostly because of their large size and immediate visible impact on human life. The best known of the vertebrates are the mammals, with about 5,500 species known and, according to experts, a few dozen remaining to be discovered. Birds have 10,000 recognized species, with an average of two or three new species turning up each year. Reptiles are reasonably well known, with slightly more than 9,000 species recognized and 1,000 estimated to await discovery. Fishes have 34,000 known species and as many as 10,000 awaiting discovery. Amphibians (frogs, salamanders, wormlike caecilians), among the most vulnerable to destruction, are less well known than the other land vertebrates: a bit over 6,600 species discovered out of a surprising 16,000 believed to exist. Flowering plants come in with about 270,000 species known and as many as 94,000 awaiting discovery.

For most of the rest of the living world, the picture is radically different. When expert estimates for invertebrates (such as the insects, crustaceans, and earthworms) are added to estimates for algae, fungi, mosses, and gymnosperms as well as for bacteria and other microorganisms, the total added up and then projected has varied wildly, from 5 million to more than 100 million species.

If the current rate of basic descriptions and analyses continues, we will not complete the global census of biodiversity—what is left of it—until well into the 23rd century. Further, if Earth’s fauna and flora is not more expertly mapped and protected, and soon, the amount of biodiversity will be vastly diminished by the end of the present century. Humanity is losing the race between the scientific study of global biodiversity and the obliteration of countless still-unknown species.

5

From 1898 to 2006, 57 kinds of freshwater fish declined to extinction in North America. The causes included the damming of rivers and streams, the draining of ponds and lakes, the filling in of springheads, and pollution, all due to human activity. Here, to bring them at least a whisper closer to their former existence, is a partial list of their common names: Maravillas red shiner, plateau chub, thicktail chub, phantom shiner, Clear Lake splittail, deepwater cisco, Snake River sucker, least silverside, Ash Meadows poolfish, whiteline topminnow, Potosi pupfish, La Palma pupfish, graceful priapelta, Utah Lake sculpin, Maryland darter.

There is a deeper meaning and long-term importance of extinction. When these and other species disappear at our hands, we throw away part of Earth’s history. We erase twigs and eventually whole branches of life’s family tree. Because each species is unique, we close the book on scientific knowledge that is important to an unknown degree but is now forever lost.

The biology of extinction is not a pleasant subject. The vanishing remnants of Earth’s biodiversity test the reach and quality of human morality. Species brought low by our hand now deserve our constant attention and care.

6

How fast are we driving species to extinction? For years paleontologists and biodiversity experts have believed that, before the coming of humanity about 200,000 years ago, the rate of origin of new species per extinction of existing species was roughly one species per million species per year. As a consequence of human activity, it is believed that the current rate of extinction overall is between 100 and 1,000 times higher than it was originally.

This grim assessment leads to a very important question: How well is conservation working? How much have the efforts of global conservation movements achieved in slowing and halting the devastation of Earth’s biodiversity?

Despite heroic efforts, the fact is that due to habitat loss, the rate of extinction is rising in most parts of the world. The preeminent sites of biodiversity loss are the tropical forests and coral reefs. The most vulnerable habitats of all, with the highest extinction rate per unit area, are rivers, streams, and lakes in both tropical and temperate regions.

Biologists recognize that across the 3.8-billion-year history of life, over 99 percent of all species that lived are extinct. This being the case, what, we are often asked, is so bad about extinction?

The answer, of course, is that many of the species over the eons didn’t die at all—they turned into two or more daughter species. Species are like amoebas; they multiply by splitting, not by making embryos. The most successful are the progenitors of the most species through time, just as the most successful humans are those whose lineages expand the most and persist the longest. We, like all other species, are the product of a highly successful and potentially important line that goes back all the way to the birth of humanity and beyond that for billions of years, to the time when life began. The same is true of the creatures still around us. They are champions, each and all. Thus far.

7

The surviving wildlands of the world are not art museums. They are not gardens to be arranged and tended for our delectation. They are not recreation centers or reservoirs of natural resources or sanatoriums or undeveloped sites of business opportunities—of any kind. The wildlands and the bulk of Earth’s biodiversity protected within them are another world from the one humanity is throwing together pell-mell. What do we receive from them? The stabilization of the global environment they provide and their very existence are gifts to us. We are their stewards, not their owners.

Each ecosystem—be it a pond, meadow, coral reef, or something else out of thousands that can be found around the world—is a web of specialized organisms braided and woven together. The species, each a freely interbreeding population of individuals, interact with a set of the other species in the ecosystem either strongly or weakly or not at all. Given that in most ecosystems even the identities of most of the species are unknown, how are biologists to define the many processes of their interactions? How can we predict changes in the ecosystem if some resident species vanish while other, previously absent species invade? At best we have partial data, working off hints, tweaking everything with guesses.

What does knowledge of how nature works tell us about conservation and the Anthropocene? This much is clear: To save biodiversity, it is necessary to obey the precautionary principle in the treatment of Earth’s natural ecosystems, and to do so strictly. Hold fast until we, scientists and the public alike, know much more about them. Proceed carefully—study, discuss, plan. Give the rest of Earth’s life a chance. Avoid nostrums and careless talk about quick fixes, especially those that threaten to harm the natural world beyond return.

8

Today every nation-state in the world has a protected-area system of some kind. All together the reserves number about 161,000 on land and 6,500 over marine waters. According to the World Database on Protected Areas—a joint project of the United Nations Environment Programme and the International Union for Conservation of Nature—they occupied by 2015 a little less than 15 percent of Earth’s land area and 2.8 percent of Earth’s ocean area. The coverage is increasing gradually. This trend is encouraging. To have reached the existing level is a tribute to those who have participated in the global conservation effort. But is the level enough to halt the acceleration of species extinction? It is in fact nowhere close to enough.

The declining world of biodiversity cannot be saved by the piecemeal operations in current use. It will certainly be mostly lost if conservation continues to be treated as a luxury item in national budgets. The extinction rate our behavior is imposing, and seems destined to continue imposing, on the rest of life is more correctly viewed as the equivalent of a Chicxulub-size asteroid strike played out over several human generations.

The only hope for the species still living is a human effort commensurate with the magnitude of the problem. The ongoing mass extinction of species, and with it the extinction of genes and ecosystems, ranks with pandemics, world war, and climate change as among the deadliest threats that humanity has imposed on itself. To those who feel content to let the Anthropocene evolve toward whatever destiny it mindlessly drifts to, I say, please take time to reconsider. To those who are steering the growth of nature reserves worldwide, let me make an earnest request: Don’t stop. Just aim a lot higher.

Populations of species that were dangerously small will have space to grow. Rare and local species previously doomed by development will escape their fate. The unknown species will no longer remain silent and thereby be put at highest risk. People will have closer access to a world that is complex and beautiful beyond our present imagining. We will have more time to put our own house in order for future generations. Living Earth, all of it, can continue to breathe.

Drain the narrative of hate for empathy

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in– Leonard Cohen

More and more false news stories invade the press and the internet, so much so that Facebook, after being criticized for potentially aiding Trump’s victory by the plethora of fake news, is now to take action and rein in this scourge. No wonder then that Oxford Dictionaries has named the adjective ‘post-truth’ as its word of the year. Post-truth (usually associated with politics) is defined as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief”. Climate denial (assertion that science is merely an opinion amongst many), religious fanaticism and extreme nationalism all feed off appeals to disregard peer-reviewed science, compassion for the other and fairness. Whereas ‘propaganda’ was associated with the promulgation of falsity in war time, post-truth has invaded most discussions: enter Trump and the nasty election rhetoric that enfolded a democratic process in hate, misogyny, misinformation and extremist viewpoints that threaten to unhinge an already polarized society.

No one should be surprised then that the motto “Drain the swamp”, chanted by Trump and supporters, was based on the false notion that Washington, D.C. was built on a swamp. His desire to get rid of the bureaucracy in Washington by metaphorically draining a human swamp has no basis in the District’s physical past. More importantly, swamps have enormous biodiversity and are part of an ecology that keeps us all alive, and disdain for our unique planet’s vibrant life systems has its consequences.

The ubiquitous false news finds its way to the natural-gas ventures in British Columbia via the large oil producers. A corporate-funded study was rejected by the federal government, but the project was approved anyway in September and now faces many lawsuits. It turns out that salmon use the area far more than was revealed. Now Kinder Morgan’s pipeline may be approved by this ‘climate-friendly’ government.

The month of November 2016 hasn’t been buoyed by optimism for our planet. The UN Climate Summit in Marrakech, following the more hopeful although flawed Paris summit in 2015, heard scientists proclaim the most pessimistic declarations for planetary stability; the announcement that 2016 has a 90% chance of being the warmest year on record in modern times doesn’t help the prognosis that this century will not be kind to our children or our grandchildren. The Arctic, going into polar night, is 20 °C above its normal temperature. In response to a climate-denier president-elect in the USA, the Marrakech Action Proclamation affirmed the urgency for governments to commit to fossil fuel reductions to prevent further global warming. Obama’s climate envoy suggested that there could easily be a sea-level rise of 1.5 metres by 2050 as a result of rapid polar warming.

Sadly, our Minister of the Environment at Marrakech gave only 15 minutes to the Canadian Youth Climate Coalition to state their case for Indigenous Peoples and youth affected by climate change, but had an hour to speak with the oil industry.

Dehumanizing, writes philosopher and humanist Charles Eisenstein, is the surest path to war. “The truth can only be sourced from the sincere question, ‘What is it like to be you?’ That is called compassion, and it invites skills of listening, dialog, and communicating without violence or judgement.”